Design of a Tourist Communication Plan that Shows the Matrilineal Cultural Heritage of the Bribri People (Talamanca, Costa Rica)

Diseño de un plan de comunicación turística que muestre el patrimonio cultural matrilineal del pueblo Bribri (Talamanca, Costa Rica)

Revista Trama

Volumen 10, número 2

Julio - Diciembre 2021

Páginas 43-66

ISSN: 1659-343X

https://revistas.tec.ac.cr/trama

Nadia Alonso López 1 / Maryland Morant Gonzáles 2/ Cristina Navarro Laboulais 3

Fecha de recepción: 31 de mayo, 2021.

Fecha de aprobación: 22 de abril, 2022.

Alonso, N., Morant, M. y Navarro, C. (2021). Design of a Tourist Communication Plan that Shows the Matrilineal Cultural Heritage of the Bribri People (Talamanca, Costa Rica). Trama, Revista de ciencias sociales y humanidades, Volumen 10, (2), Julio-Diciembre, págs. 43-66.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18845/tramarcsh.v10i2.6303

Resumen

Esta investigación desarrolla un plan de comunicación turística para la comunidad indígena Bribri. Los principales objetivos del plan son atraer turismo de calidad mostrando el patrimonio cultural inmaterial de los Bribi y ayudar así a preservar su cultura. Se utiliza una metodología analítico-descriptiva basada en el análisis del entorno y la definición de acciones a través de procesos participativos con la comunidad. Estos procesos están orientados al empoderamiento de las mujeres indígenas.

Los Bribri viven en el cantón de Talamanca (Costa Rica). Los Bribi y otras etnias de la zona se distinguen de las comunidades vecinas porque presentan una estructura social matrilineal. Su economía se basa en la agricultura, a lo que se ha sumado un incipiente turismo.

Para hacer perdurar su patrimonio cultural, los Bribri están implementando diversas acciones en colaboración con la Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV) y el Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica (TEC). Estas acciones incluyen el desarrollo de este plan de comunicación, que tiene como objetivo preservar la impronta de la cultura Bribri y desarrollar un método que pueda ser utilizado por otras comunidades indígenas con características similares.

Palabras clave: Plan de comunicación, difusión turística, cooperación, comunidad indígena.

Abstract

This research develops a tourism communication plan for the indigenous Bribri community. The main objectives of the plan are to attract quality tourism by showcasing the intangible cultural heritage of the Bribi and so help preserve their culture. We use an analytical-descriptive methodology based on an analysis of the environment and a definition of actions through participatory processes with the community. These processes are oriented towards the empowerment of indigenous women.

The Bribri live in the canton of Talamanca (Costa Rica). The Bribi and other ethnic groups in the area can be distinguished from neighbouring communities because they have a matrilineal social structure, and their economies are based on farming – to which has been added an incipient tourism.

To enhance the durability of their cultural heritage, various actions are being implemented by the Bribri in collaboration with the Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV) and the Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica (TEC). These actions include the development of this communications plan – which aims to preserve the imprint of Bribri culture and develop a method that can be used by other indigenous communities with similar characteristics.

Key words: Communication plan, tourism dissemination, cooperation, indigenous community.

i. introduction

All the peoples in the world have developed intangible cultural heritages. International recognition of these heritage assets as ‘melting pots of cultural diversity and guarantees of sustainable development’ (Chang, 2017) was given in 2006 with the ratification of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (UNESCO, 2003).

Intangible cultural heritage is increasingly being reinforced as an element that creates tourist interest and so may act as a motor for sustainable economic growth for small towns, territories, and indigenous communities (Gutiérrez, Such & Gabaldón, 2020; Escarré, Driha & Linditsch, 2020; Hall, 2017). These new tourist destinations provide ‘significant experiences’ to visitors, even in spaces not declared as world heritage sites, but whichshare similar characteristics.

Intangible cultural heritage is a resource in constant reformulation (a social construct) which has become a tourist product for new consumption habits in leisure societies. The increasingly frequent use of traditions, ceremonies, gastronomy, dances, music, languages, and other indigenous cultural expressions by the tourism industry has transformed intangible cultural heritage into a fundamental factor of identity and sociability. Such heritage is valued as a source of identity, diversity, creativity, practice, and knowledge – and as a social construct sustained by the richness of the society that shapes it (Hernando, 2009; López and Marín, 2010; Olivera, 2011; Boude and Luna, 2013; Flores and Nava, 2016).

Communication, tourism, and indigenous communities

In recent years, many indigenous communities have become involved in the process of tourism as ‘ancestral’ cultural societies. ‘Cultural heritage’ is recognised by UNESCO as part of an ‘economy of authenticity’ (Heinich, 2015). This phenomenon has enabled these peoples to actively defend their culture and territory through community tourism and so generate processes of cultural revitalisation and new economic opportunities (Martínez, 2017; Hale, 2002).

A pioneering study by the UNWTO (OMT, 2013) reveals the opportunities for enhancing intangible heritage and so diversifying income, the risks associated with tourism, as well as the need to design and implement sustainable tourism products based on intangible heritage. This research proposal focuses on the development of an R+D+I project granted by the Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV) in the 2019 call for ADSIDEO Projects for International Cooperation for Development. The main objective is to respond to the needs of the Bribri to improve their tourism products through participatory processes in line with identity and cultural heritage. This is a research project in the field of intangible cultural heritage and participatory processes focused on the empowerment of the local population. In addition to the UPV research team, the organisations involved in the collaboration include: the Asociación de Guías Turísticos Indígenas Bribris de Talamanca (AGITUBRIT); the Federación de Mujeres Bribris Defendiendo; and the Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica (TEC).

The Bribri indigenous community of Ditsö Kã is located in the canton of Talamanca in the province of Limón in Costa Rica. The community has 8,368 inhabitants (according to data from the most recent census in 2011) and speaks the Bribri language (although younger generations favour Spanish). The main economic activity is farming banana and cocoa, but this activity is being complemented by an incipient development of tourism (Arias and Solano, 2009; Arias, 2016). The most important difference between the Bribri and the other ethnic groups in the area is that the Bribri retain a matrilineal social structure, while the other ethnic groups have become patrilineal due to western influence.

Since 2009, at the request of the several indigenous communities, the state universities of Costa Rica have been implementing various projects addressing the needs of the indigenous communities of Talamanca. These projects promote natural and cultural tourism in a sustainable manner as a response to high rates of poverty and low levels of development.

The results of some of the projects undertaken by the country's universities reveal that tourism activities have not yet been able to organise and systematise the tourism experience. There is a lack of information and spaces for reflection on work that would facilitate the development of more activity while safeguarding intangible cultural heritages. As many authors have pointed out in various studies, the management of tourism enterprises by indigenous communities is limited by a lack of professional experience in the sector, low educational levels, and a lack of specific training among the indigenous population (Pastor & Espeso, 2015; Whitford & Ruhanen, 2014; Bennett et al., 2012; Fuller et al., 2005 and 2007; and projects Turismo en Ditsö Kã: cambio social y perspectivas de sostenibilidad, 2017-2019; Fortalecimiento de los sistemas de producción y comercialización de las unidades productivas y de servicios indígena respetando la cultura Bribri y Cabécar con un enfoque ambientalmente sostenible desarrollada en Talamanca, 2013; and Dinamizando el desarrollo de las comunidades indígenas Bribri y Cabécar de los distritos de Telire y Bratsi, 2010, all of them implemented by Universidad de Costa Rica, Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica, Universidad Nacional and Universidad Estatal a Distancia).

Given the needs identified by the project partner, it is essential to enhance the value of intangible heritage and ensure its sustainability (Seeler et al., 2021; Lorenzo & Morales, 2014). For this reason, as an integral part of the actions proposed in the ADSIDEO project, this paper focuses on a methodological proposal for the design of a tourism communication plan that enhances the heritage of the Bribri.

This plan considers the objectives and target groups, strategy, and content of the publicity measures – and indicates the expected results. The plan follows the Crea-Business-Idea initiative, which was sponsored in 2009 by the Madrid Development Institute and other national and international entities to encourage creativity in business communication.

One of the expected results is the development of a tourism model for local improvement. This model aims to enhance the tourism value of this intangible cultural heritage and empower the community and the women who play a central role (Ruiz, Arias & Solano, 2019; Arias & Morant, 2020).

It is necessary to implement a communication plan that enables wealth creation but also projects the brand of the region and its identity in relation to the matrilineal community and its intangible heritage. Social media and the production of audiovisual documents are crucial for achieving communicative success (Barrientos, Bonales & Caldevilla, 2021; Giner, 2017; Huertas, Setó- Pàmies, Míguez-González, 2015).

iI. OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY

The main objective of the project is to respond to the need of the Bribri to improve their tourism product in line with their identity and heritage. The project will use participatory processes to evaluate and record the Bribri’s cultural heritage and make an inventory.

The methodology uses techniques for community diagnosis that will help us define the tourism potential and empower the community whose women form the nucleus (Chavarochette & Rodriguez, 2020). Techniques will be used to make an inventory, evaluate, and develop sustainability indicators that relate quality of life, environmental, socio- cultural, and socio-economic parameters, as well as measuring the good use and management of available resources.

The communication plan focuses its methodology on analytical-descriptive methods based on an environmental analysis and the definition and achievement of actions, as well as the participative action of the Bribri and project members. Several authors (Hernández, 2015; Hernández & Delgado, 2013; Gómez de la Fuente, 2012; Tironi & Cavallo, 2011) refer to the relevance of tourism communication plans and implementation of actions to publicise communities at risk of exclusion by appropriately showcasing their heritage and identity. These plans improve the economy and the quality of life in the area, as well as favouring local empowerment and the capacity for autonomy in the management of cultural, economic, and social resources.

The objectives of the plan include optimising the flow of information between the project partners and organising efficient communication between the participants; as well as making the project known to potential stakeholders and the main beneficiaries (Crea Business Idea, 2009). As specific objectives, we propose showcasing the cultural features of this matrilineal society to attract visitors. We also propose ensuring the preservation of this heritage by creating and publishing audiovisual documents.

The communication plan we propose uses the AURA methodology (accompanied self-reinforcement) which was developed for the empowerment of civil societies. AURA pays particular attention to the learning process by prioritising actions or activities over material deliverables (ATOL, 2003). Its approach and methods of empowerment will enable us to develop a specific methodology that is adapted to a highly technological and hyper-connected media environment. A SWOT diagnosis will be carried out to determine the objectives and strategies of the communication plan (Tur & Monserrat, 2014) without losing sight of the global environment in terms of technology and access to information.

The various phases of the plan are to be considered from the beginning. The aim is to decide what to communicate, to whom, how, and by what means. Various stages are set:

•Message: the mission, vision, and values of the project are established after defining the intervention area and analysing strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. The message is constructed accordingly.

•Target group: reference is made both to the target group for tourism (travellers, visitors, and tourists) and to the actors who are involved in the process of tourism: organisations; agencies; tourist guides; and the media.

•Communication actions: online and offline strategies and activities are proposed. Reference has been made to elements of corporate identity and media such as social networks, websites, tourist brochures, and audiovisual material.

•Monitoring and evaluation of results: the implemented actions and the achievement of the proposed objectives will be assessed. For this purpose, we have web analysis tools, social network statistics, and statistics on visitors to the area.

iII. COMMUNICATION STRATEGY PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT PHASES

The phases proposed in the previous sections will be developed and implemented as follows.

Message

The aim is to disseminate a series of events to generate common frames of reference between those who are sending the message and those who are receiving it (Hernández & Delgado, 2013). Therefore, the message must be built from an intention to achieve a two-way information flow that links the Bribri with visitors to the area in a respectful way and without losing sight of the objective of enhancing the intangible heritage and ensuring its durability. The mission, vision, and values of the Bribri community as a tourism brand, defined in the previous participatory processes, will be used to shape this message.

•Mission: the community has a matrilineal structure and a unique cultural and intangible heritage. The aim is to make these features of the Bribri society visible and to put them in value.

•Vision: the aim is to spread the identity and cultural heritage of a matrilineal society with sustainable and quality tourism.

•Values: commitment, sustainability, harmony, balance, and generosity, values established in participatory processes.

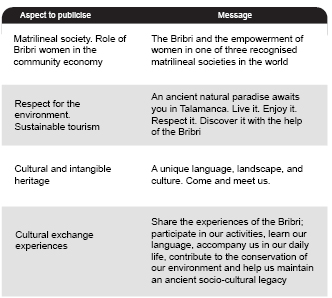

A classification is made of the aspects to disseminate and the associated messages. The definition of the messages will be as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Messages to be disseminated. Source: authors based in previous participatory processes.

Note. Messages are based on the characteristics of the Bribri community, and the mission, vision, and values defined above. Source: authors based in previous participatory processes.

Target

As this is a tourism communication plan, the direct recipients of the various actions will be potential travellers, visitors, and tourists in the area. It is possible to define a standard profile of the target audience on the mission, vision and values set out above. These would-be tourists have interests that go beyond sun, sand, and nightlife. The target audience are visitors interested in culture, art and nature, and are concerned about sustainability and the environment. They have a high level of social awareness and hope to participate in the improvement of the communities visited. For this reason, the proposed messages focus on social, cultural, and environmental aspects. Accessibility to the Talamanca area where the Bribri reside must also be considered, as well as potential difficulties for people with reduced mobility.

The internal targets for tourism diffusion include:

•Tourist agencies and guides in the area.

•Tourist operators.

•Online publications of trips and tourist destinations.

•Local, provincial, and national government institutions.

•Specialised media.

•Media in general.

Communication actions

It is relevant to consider the concept of community ethics, which refers to the affirmation and recognition of the identity of groups without controlling or dominating them (Xinico, 2011). Applied to communication, the idea is to propose actions that establish a horizontal and participative relationship with the Bribri, respecting their values and identity while counting on their presence and intervention in communication actions and messages, as explained in Section 3.1. Therefore, we have started by appointing two people responsible for jointly supervising the implementation and execution of the plan: one is a member of the Bribri and the other is an external monitor. A final year student of tourism at the Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica is proposed as an external monitor. The Bribri will nominate their own participant.

Two lines of action are proposed to respond to the target groups:

•Internal communication: information management tools connecting the individuals in charge of implementing the communication plan and members of the Bribri.

•External communication: corporate identity elements, online and offline communication actions.

Internal communication

The aim is to create and provide tools for sharing information by project participants from the university, the Bribri, and tourism operators. Specifically, files stored in the cloud will be shared and virtual meetings organised to discuss the implementation and monitoring of the plan. It is important to schedule meetings well in advance due to the difficulties of network connectivity in the Talamanca region. The possibility of face-to-face meetings between project members is also considered.

External communication

The external communication strategy begins with the design of the elements of corporate image, specifically, the logo that will define the Bribri as a tourism brand. It must be considered that the logo will be the main image that defines the project based on its mission, vision, values, and messages. All image aspects will have three key factors in common: remembrance, simplicity, and versatility (Costa, 2004). With this premise, two proposals are made:

•Convene a competition among graphic design students at the University of Costa Rica. In this way, the university community is involved in the tourist promotion of its own heritage.

•Convene a competition among professional associations of graphic designers in countries likely to send visitors to the area. In this way, the Bribri are made known internationally and graphic design professionals are involved. A study will be needed on countries and associations that should be involved in the initiative.

In both cases, it will be necessary to decide rules for the competition and the prize for the chosen design.

The online communication actions are proposed from the base of the mentioned community ethics, that is, counting on the participation of the Bribri, and with the objective of showcasing and preserving their intangible cultural heritage. The contents will be further explained later. The following actions are proposed:

•Creation of a website: a corporate website continues to be one of the most widely used instruments for creating awareness of an organisation, as well as being one of the elements that produces the greatest differentiation (López & Moreno, 2019). In this case, the creation of a website is proposed as a tool for the tourist diffusion of the Bribri. This website must have a previously chosen logo and respect the corporate colours proposed in its design. It will have sections about the history of the Bribri, language, matrilineal society, curiosities, environmental surroundings, tourist routes in the area, and questions to consider before visiting (such as access). Contact details and testimonials from tourists and visitors to the area will also be included (by video if possible). In general, audiovisual elements should be the basis for the design of the website. Likewise, the creation of a team, which may report to a manager at the University of Costa Rica, should be considered for the creation, maintenance, and funding of the website.

•Audiovisual material: it is important to highlight the importance of audiovisual material for the project. The use of video is a growing trend on the internet (Costa-Sánchez, 2018) and it must be included in any communication strategy to provide visibility. Specifically, we propose making a documentary about the Bribri with the active participation of the community. The documentary will explain the history of the community and its modus vivendi, as well as socio- cultural, environmental, and matriarchal aspects. In addition, the life stories of Bribri women will be included, highlighting the matrilineal nature of the community. This documentary will be published in full on the website and on other channels described below. In a second phase, individual audiovisual pieces with the life stories of Bribri women, tourist routes, and cultural traditions will be posted.

Visitors will be invited to record themselves explaining their experience when visiting the Bribri. Visitors can then send their testimonies to the email address that will appear on the website or through the associated social networks. These testimonies will be published on the website and social networks.

Social networks and video platforms: profiles will be created on social networks associated with the website (but which will operate independently of the website). Given the importance of the audiovisual part of the communication plan, it is proposed to create an account on the Instagram social network and a YouTube channel. In the case of Instagram, this is justified because it is an eminently visual network, as well as being the fastest growing network in number of users (We Are Social, 2020). Specifically, it is proposed to create a company account since this enables the description to be categorised, contact details to be included, and the results of the publications to be measured statistically. The account will publish photographs and audiovisual pieces on the area, as well as testimonials from visitors and recommendations from tourist guides. The material for the publications will be provided by the same audiovisual material as the documentary, the tourist guides, and members of the Bribri. The periodicity and theme of the publications will be established in a content planning tool. The Bribri will participate in the planning and selection of proposals. The name of the account is yet to be decided.

YouTube is the most popular internet platform for audiovisual content (AIMC, 2019) and so it is necessary to create a YouTube channel for the diffusion of the Bribri among potential tourists. The documentary – as well as the individual audiovisual pieces and visitor testimonies – will be published on YouTube and organised in playlists with the corresponding keyword categorisation. The channel will be identified with the logo and the name agreed with the Bribri. As in the case of the website, a team will be needed to manage the Instagram account and YouTube channel.

Offline actions include designing promotional materials – specifically, brochures with photographs and information about the Bribri that highlight the proposed values – which focus on the messages mentioned above. The brochures will also include the logo and corporate identity elements, contact details, web address, Instagram profile name, and YouTube channel name. These brochures will be distributed to hotels, tourist residences, and travel agencies in Costa Rica.

It is also proposed to hold awareness seminars, roundtables, and conferences about the Bribri at the University of Costa Rica. Environmental and cultural workshops in the same Bribri community can also be recorded and the resulting audiovisual material can be used on the web and social networks.

Dissemination

Once the actions and channels have been established, the aim is to make them visible. To this end, various actions are proposed:

•Study the tour operators offering trips to the area with a visitor profile as proposed above. Once defined, a presentation email will be sent together with a digital brochure and a link to the project’s website and social networks.

•Study the various electronic magazines, blogs, and specialised travel media. Once defined, an email presentation will be sent together with a digital brochure, a link to the project’s website and social networks, and a proposal (in the form of a press release) for content to be published. Content about the project that can be published on these sites.

•Study of travel influencers on Instagram. Contact by direct message with a proposal to spread the audiovisual content generated.

•Creation of a label or hashtag defining the project for Instagram. Use labels that use accounts related to the project.

•Study of documentary contests made for this communication plan.

•Distribution of printed brochures in hotels, tourist residences, travel agencies, tourist establishments, and organisations in Costa Rica

•Creation of an audiovisual dossier with material to distribute among tour operators and guides in the area.

Results and evaluation of monitored activities

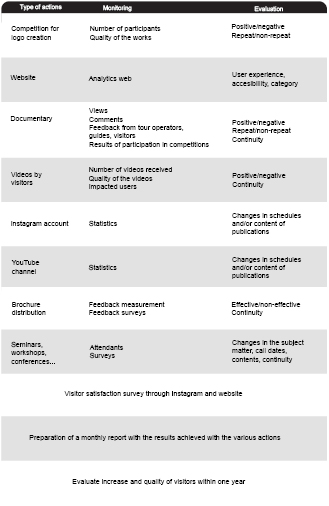

It is essential to evaluate the strategies and actions carried out to discover the strengths and weaknesses of the plan and observe which actions have been successful and impacted on the target audience (Tur & Monserrat, 2014). It is proposed to create a methodology for evaluating the project based on the parameters detailed in Table 2. As can be seen, the type of action carried out, the monitoring process, and the resulting evaluation of the monitoring actions are explained. In the case of online actions (such as the creation of a website, an Instagram account, and a YouTube channel) the monitoring and measurement of results will be carried out using web analytics and statistics provided by the social networks. User experiences, accessibility, changing or maintaining the categories of the website, and changes in schedules and contents of publications will be evaluated. The number of videos received from visitors, their quality, and the impact they have on website visitors and social networks users will be measured. Based on these measurements, it will be evaluated whether the action is positive or negative and its continuity. A follow-up will be made of the documentary and the visualisations and comments on social networks; and feedback from operators, tourist guides, and visitors will be evaluated. In this way, the suitability or otherwise of these actions, their continuity, and the possibility of making a second documentary in the long term will be decided. As for the logo competition, based on the number of participants and the quality of the proposals received, the suitability of the action will be evaluated and the possibility of holding similar competitions in the future will be considered.

For offline actions such as the distribution of brochures, establishments will be monitored with telephone interviews and the completion of online surveys to assess the suitability of the actions and evaluate their continuity. In conferences, workshops, and seminars, the number of attendees, and the results of surveys will be monitored to evaluate continuity and possible changes in subject matter, dates, and content.

Likewise, surveys will be carried out on visitors through the Instagram account and website. To evaluate the effectiveness of these actions, an essential question in these surveys is how the Bribri are perceived by visitors. A monthly report with results of the actions and an annual report will evaluate the increase in number and quality of visitors.

Various audiovisual materials (including a medium-length documentary and shorter independent audiovisual pieces) will be positioned for use in local tourism agencies, social networks, or other supports. It is also planned to present the documentary in various events such as the Indigenous Peoples' Film Festival, the International Social Film Festival, and AriDoc.

Table 2. Action evaluation. Source: authors

VI. Conclusions

The Bribri, like other communities at risk of exclusion, could see its identity as a tourist destination boosted through the various actions proposed in this communication plan. Firstly, it is essential to define the brand of the location and give it personality as a tourist destination by highlighting its intangible cultural heritage. The targets are tourists and visitors, as well as tour operators, guides, and the media. Given the current media environment (characterised by technological advances, hyper-connectivity, and the boom in video) great importance will be given to social media and audiovisuals – but without leaving aside offline sources. Likewise, two elements are fundamental: the design of a corporate identity that defines the Bribri and an emphasis on dissemination actions that showcase this community. The communication plan will be continuously reviewed and results monitored so that actions can be modified according to the achievement of the proposed objectives.

The need to design a communication plan for the tourist dissemination of communities at risk of exclusion is highlighted. However, the characteristics and particularities of each community must be considered. To this end, this research can be the starting point for the creation of a methodology for the development of communication plans adapted to each community.

The limitations of this research are that, despite the existence of a large bibliography on tourism communication plans, there is little literature on communication plans that enhance the value of indigenous intangible cultural heritage, and even less has been published on implemented proposals. The published studies do not offer proposals with results that enable extrapolation to other case studies, or an assessment of the positive or negative impact of these plans on indigenous communities. For this reason, it is considered that this work represents an initial methodological proposal to be followed with future research.

V. References

ATOL vzw (2003), L’AURA ou l’auto-renforcement accompagné. Guide d’accompagnement. Leuven.

Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación [AIMC] (2019). Audiencia de Internet en el EGM. AIMC. Recuperado 28 abril 2020 de http://internet.aimc.es/index.html#/main/sitiosinternet

Arias, D. y Solano, J. (2009). Programa de capacitación para guías turísticos locales en territorio indígena de Talamanca [Proyecto de graduación para la obtención de bachillerato en gestión de turismo]. Costa Rica. ITCR.

Arias, D. (2016). Turismo: un aporte fundamental en el territorio indígena talamanqueño. Investiga TEC, 1, 8-13.

Arias, D. y Morant, M. (2020): Patrimonio cultural inmaterial indígena: análisis de las potencialidades turísticas de los simbolismos del cacao del pueblo Bribri (Talamanca, Costa Rica). Cuadernos de Turismo, 46, pp. 505-530.

Barrientos Báez, A., Bonales Daimiel, G., & Caldevilla-Domínguez, D. (2021). The tourist ecosystem through social networks. TECHNO REVIEW. International Technology, Science and Society Review, 10(2), pp. 97-109. https://doi.org/10.37467/gka-revtechno.v10.3010

Bennett, N., Lemelin, R. H., Koster, R. & Budke, I. (2012). A capital assets framework for appraising and building capacity for tourism development in aboriginal protected area gateway communities. Tourism Management, 33 (4), 752-766.

Boude, O. y Luna, M. (2013). Gestión del conocimiento salvaguardia del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial del Carnaval de Barranquilla. Revista de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales, 71, 27-44.

Costa, J. (2004). La imagen de marca: un fenómeno social. Barcelona. Paidós.

Costa-Sánchez, C. (2018). Audiovisual interactivo. Del vídeo a los vídeos corporativos. En: C. Costa-Sánchez y S. Martínez (Eds.). Comunicación corporativa audiovisual y online. Innovación y tendencias. Barcelona: UOC.

Crea Business Idea. (2009). Manual de creatividad empresarial. Recuperado el 25 de abril de 2020 de https://docplayer.es/6973936-Manual-de-la-creatividad-empresarial.html

Chang, G. (2017). Diagnóstico del patrimonio cultural intangible de Costa Rica: instrumento para reconocer la diversidad cultural. InterSedes, 18 (37)1-14.

Chavarochette, C. et Rodriguez, T. (2020). Les territoires du cacao biologique, alternatives productives et femmes indigènes, Talamanca, Costa Rica. Études caribéennes, 45-46. https://doi.org/10.4000/etudescaribeennes.18486

Escarré Urueña, R., Driha, O.M. y Linditsch, C. (2020). Cooperación internacional en educación superior para el turismo sostenible. Estudios y perspectivas en turismo, 29(4), 1096-1114.

Flores, G. y Nava, E. F. (2016). Identidades en venta. Músicas tradicionales y turismo en México. UNAM: Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales.

Fuller, D., Buultjens, J. & Cummings, E. (2005). Ecotourism and indigenous micro-enterprise formation in Northern Australia opportunities and constraints. Tourism Management, 26(6), 891-904.

Fuller, D., Caldicott, J., Cairncross, G. & Wilde, S. (2007). Poverty, Indigenous culture and ecotourism in remote Australia. Development, 50(2), 141- 148.

Giner Sánchez, D. (2017). Social media marketing en destinos turísticos: implicaciones y retos de la evolución del entorno online. Barcelona: UOC.

Gómez de la Fuente, M. C. (2012). Auditoría de comunicación en las organizaciones. Aplicación de un modelo en dos organizaciones del noroeste de México [Tesis doctoral]. Santiago de Compostela, España. Universidad de Santiago de Compostela.

Gutiérrez Cruz, M., Such Devesa, M. J., y Gabaldón Quiñones, P. (2020). La mujer emprendedora en el turismo rural: peculiaridades del caso costarricense a través de la revisión bibliográfica. Cuadernos de Turismo, (46), 185–214. https://doi.org/10.6018/turismo.451691

Hale, C. (2002). Does Multiculturalism Menace? Governance, Cultural Rights and the Politics of Identity in Guatemala. Journal of Latin American Studies, 34, 485-524.

Hall, I. (2017). De la colectividad a la comunidad. Reflexiones acerca del derecho de propiedad en Llanchu, Perú. Revista de Antropología Social, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.5209/RASO.57611

Heinich, N. (2015). La fabrique du patrimoine. De la cathedrale à la pètite cuillere. Les éditions de la MSH.

Hernández, I. y Delgado, G. (2013). Diseño de una estrategia de comunicación basada en el uso de las redes sociales para la difusión del turismo alternativo con identidad indígena. Correspondencias & Análisis, 3, 35- 54.

Hernández, P. (2015). Bases para un plan de comunicación estratégica de un proyecto de turismo indígena en la región metropolitana de Santiago de Chile [Tesis doctoral]. Santiago de Chile, Chile. Universidad Academia de Humanismo Cristiano.

Hernando, A. (2009). El patrimonio: entre la memoria y la identidad de la Modernidad. Revista ph, 70, 88-97.

Huertas, A., Setó-Pàmies, D. y Míguez-González, M. I. (2015). Comunicación de destinos turísticos a través de los medios sociales. El Profesional de la Información, 24(1), 15-21.

López, Á. y Marín, G. (2010). Turismo, capitalismo y producción de lo exótico: una perspectiva crítica para el estudio de la mercantilización del espacio y la cultura. Relaciones Estudios de Historia y Sociedad, 31, 219–258. http://dx.doi.org/10.24901/rehs.v31i123.648

López, E. y Moreno, B. (2019). La web corporativa como herramienta estratégica para la construcción de la identidad municipal: análisis de los municipios rurales en España. El Profesional de la Información, 28(5), 1- 16.

Lorenzo Linares, H., y Morales Garrido, G. (2014). Del desarrollo turístico sostenible al desarrollo local. Su comportamiento complejo. PASOS Revista De Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 12(2), 453-466. https://doi.org/10.25145/j.pasos.2014.12.033

Martínez Quintana, V. (2017). El turismo de naturaleza: un producto turístico sostenible. Arbor, 193(785). https://doi.org/10.3989/arbor.2017.785n3002

Olivera, A. (2011). Patrimonio inmaterial, recurso turístico y espíritu de los territorios. Cuadernos de Turismo, 27, 663-677.

Organización Mundial del Turismo [OMT] (2013). Turismo y patrimonio cultural inmaterial. Madrid: OMT.

Pastor, M. J. y Espeso-Molinero, P. (2015). Capacitación turística en comunidades indígenas. Un caso de Investigación Acción Participativa (IAP). El Periplo Sustentable, 9, 171-208.

Ruiz Fernández, A.R., Arias Hidalgo, D. & Solano Brenes, J. (2019). Bribri Kinship Relations: The Social Implications of a Matrilineal System. In: Ortega-Rodríguez M. & Solís-Sánchez H. (eds.), Costa Rican Traditional Knowledge According to Local Experiences. 127-141. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-06146-3_9

Seeler, S., Zacher, D., Pechlaner, H. & Thees, H. (2021). Tourists as reflexive agents of change: proposing a conceptual framework towards sustainable consumption. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2021.1974543

Tironi, E. y Cavallo, A. (2011). Comunicación estratégica. Vivir en un mundo de señales. Santiago de Chile. Taurus.

Tur, V. y Monserrat, J. (2014). El plan estratégico de comunicación. Estructura y funciones. Razón y palabra, 88, 1-18.

UNESCO (2003). Convención para la salvaguardia del patrimonio cultural inmaterial 2003. https://ich.unesco.org/es/convenci%C3%B3n

We are Social (2020). Digital 2020: Global Digital Overview. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-global-digital-overview

Whitford, M. & Ruhanen, L. (2014). Indigenous tourism businesses: An exploratory study of business owner perceptions of drivers and inhibitors. Tourism Recreation Research, 39, 2, 149-168.

Xinico, Á. (2011). Estrategia de comunicación para promover la participación de la mujer indígena a nivel comunitario a través de Comkades del municipio de San Martín Jilotepeque, Chimaltenango. [Tesis doctoral]. Guatemala. Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala.

1. Profesora-Investigadora de la Universitat Politècnica de València. Valencia, España. Departamento de Comunicación Audiovisual, Documentación e Historia del Arte

Correo electrónico: naallo1@har.upv.es

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5220-2232

2. Profesora-Investigadora de la Universitat Politècnica de València. Valencia, España. Departamento de Ingeniería Cartográfica, Geodesia y Fotogrametría.

Correo electrónico: marmogon@cgf.upv.es

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2339-9133

3. Profesora-Investigadora de la Universitat Politècnica de València. Valencia, España. Departamento de Lingüística Aplicada

Correo electrónico: cnavarro@idm.upv.es

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8620-4087