This study analyzes the evolution of occupational illnesses and their causing agents in Spain during 2009-2020, paying close attention to territorial and industrial trends.

Workplace safety is an increasingly important topic around the world with important economic and societal implications (Kivimäki et al., 2015; ILO, 2019; Lafuente & Abad, 2021). In this sense, governments and organizations are increasingly deploying resources to support respectively policies and practices that help stimulate social wealth and enhance work environments (Piore & Schrank, 2018; Lafuente & Daza, 2020; Lafuente & Abad, 2021). In this sense, perhaps because of data availability issues, underlying the design of such policies and practices is the common assumption that work accidents and illnesses can be treated and analyzed under a homogeneous framework. But, work accidents and occupational illnesses result from heterogeneous processes and entail different consequences on workers’ health (Takala et al., 2014; Toivanen et al., 2019). Besides, although progress has been made in reducing work related accidents and illnesses; work risks have not been reduced in a uniform way leaving some workers, organizations and industries overexposed to these risks (European Commission, 2021). Furthermore, the typology of work risks is changing due to a number of factors, including technological innovation, variations in the organization of production, and the restructuring of labor markets (greater flexibility, new types of contracts, the increased rate of working women, immigration waves, among others) (Kalleberg, 2012; Takala et al., 2014; Kivimäki et al., 2015).

This implies that the approach to work accidents and illnesses based on a common framework is potentially causing an under-reporting of illnesses’ effects because of the lack of specific information on prevailing industries and the potential connections between work environments and health outcomes. Also, the joint analysis of work accidents and occupational illnesses affects their monitoring by failing at disaggregating data that permits to capture the specific magnitude of their safety problems, to set policy priorities and to target interventions to enhance safety at the workplace (Leigh et al., 2001; Bofinger, 2005; Bhattacharya, 2014; Cioni & Savioli, 2016).

The structure of current data systems has many times conditioned research efforts. Most studies specifically dealing with work safety issues at national or sub-national levels have focused on either the study of work accidents or the aggregate analysis of work accidents and illnesses (Lafuente & Abad, 2021).

Because of the increased importance and visibility of occupational illnesses, as well as the value of accessing more detailed data, research addressing occupational illnesses has grown during the last decade (Trinkoff et al., 2006; Bhattacharya, 2014; Kivimäki et al., 2015; Toivanen et al., 2019; Cioni & Savioli, 2016).

Whereas the causes and consequences of occupational illnesses to workers’ health have been extensively analyzed (Trinkoff et al., 2006; Quandt et al., 2006; Bhattacharya, 2014; Kivimäki et al., 2015), comparatively few studies have examined occupational illnesses from a managerial, territorial or industrial perspective, relative to work accidents. Concretely, the main research stream on occupational illnesses mostly evaluates their prevalence in a single industry (e.g., agriculture, poultry, health care, construction, and consumer services), and has focused on, among others, musculoskeletal disorders (Quandt et al., 2006; Trinkoff et al., 2006; Bhattacharya, 2014), heart conditions (Kivimäki, 2015; Toivanen et al., 2019), and skin disorders, cuts and burns (Turjanmaa, 1987; Bofinger, 2005; Noe et al., 2007; Muula et al., 2010; Stocks et al., 2012; Zorba et al., 2013). Few studies have evaluated the incidence of occupation illnesses in multiple industries (Dembe, 2005; Zorba et al., 2013; Bhattacharya, 2014).

Overall, this research offers relevant findings that point to the social and economic value of job safety. First, these studies support the notion that the relative under-reporting of occupation illnesses is caused by delayed diagnosis related to symptom appearance and the physical and mental degeneration of workers’ health condition (Zorba et al., 2013; Bhattacharya, 2014). Second, prior work found that labor intensive industries are more prone to show higher levels of occupational illnesses, including for example, primary industries such as agriculture and poultry (Quandt et al., 2006; Muula et al., 2010), construction (Stocks et al., 2012), and consumer services sectors (Zorba et al., 2013).

Third, weak safety regulations (lack of ergonomic guidelines and programs, and poor regulatory tools to classify occupational illnesses) together with a low monitoring of businesses’ work practices (long working hours, lack of internal safety controls) increase workers’ vulnerability and, subsequently, the prevalence of occupational illnesses (Dembe et al., 2005; Quandt et al., 2006; Muula et al., 2010).

Although it falls outside the scope of this study, it is worth mentioning a second research line-rooted in the fields of economics and healthcare-that deals with work safety from a policy viewpoint. Studies in this tradition mostly focus on the role of economic fluctuations and safety controls on both work accidents and illnesses (Asfaw et al., 2011; Boone et al., 2011; Fernández-Muñiz et al., 2018; Piore & Schrank, 2018; Lafuente & Daza, 2020; Lafuente & Abad, 2021).

From a societal perspective the study of occupational illnesses should be included in the agenda of scholars and social planners. Nevertheless, much work is needed in order to increase our knowledge both on the incidence of specific illnesses in different industries and on the temporal evolution of occupational illnesses in territories with different industrial and social traditions.

Occupational illnesses are at the center of this study, and the proposed analysis of the evolution of occupational illnesses in Spain from 2009 to 2020 pays close attention to differences and trends at the territorial level and at the industrial level. In particular, by describing the temporal trajectory of work-related illnesses this study attempts to document the patterns of occupational illnesses across heterogeneous territories-i.e., Spain’s Autonomous Communities-and across industries. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first study that specifically deals with the descriptive analysis of occupational illnesses in Spain. Despite its utter simplicity, the approach adopted in this paper seeks to offer novel evidence that enriches our knowledge on occupational illnesses and their potential incidence in different economic and industrial settings.

The plan of the paper follows. Section 2 describes the data and variable definition, while the findings are offered in Section 3. Finally, Section 4 presents the concluding remarks, policy implications, and future research lines.

2. Data and variable definition

2.1 Data

The data used in this study was collected from the annual reports of the General Office of Statistics on Occupational Illnesses of the Spanish Ministry of Employment and Social Security (https://w6.seg-social.es/PXWeb_NCIP/pxweb/es/Enfermedades%20profesionales/ ).

These reports contain specific data on the number of medically certified occupational illnesses suffered by workers affiliated to the social security regime. Available information includes the breakdown of occupational illnesses by territory, industry, and the causing agent of the documented work-related illnesses.

The final dataset contains information for the period 2009-2020. For the study period, the data was collected for two different groups of interests. First, the geographic group includes the 17 Autonomous Communities that form Spain (NUTS-2). Second, the economic group splits the data into five industries: 1) primary industries (i.e., agriculture, livestock farming, forestry, and fishing), 2) manufacturing, 3) construction, 4) retail (wholesaling and retail sale), and 5) services (professional and consumer oriented).

2.2 Variable definition

Before presenting the variables used in this study, it is important to offer a definition of occupational illness. Based on the Royal Decree 08/2015 (art. 157) (BOE, 2015), “an occupational illness is defined as that contracted by employees from work activities specified in the table developed and approved in this Law, and that is caused by the action of the elements or substances indicated in the said table for each type of occupational illness”.

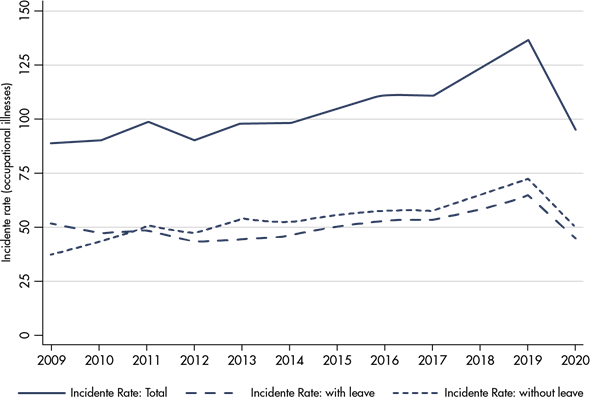

With this definition in hand, for the analysis the following variables were extracted from the databases. First, the incidence rate (IR), which is calculated as the number of occupational illnesses per one hundred thousand workers (illnesses/100,000 workers). Additionally, the IR was split into two categories: occupational illnesses with work leave and occupational illnesses without work leave. This classification is a good proxy measure of the severity level and expected duration of occupational illnesses.

Second, the study includes the average number of days away from work (AL), which is computed as the number of days of work leave of all closed occupational illness files. The time window for this variable includes the total time (in days) elapsed between the day the occupational illness is notified until the day that the file is closed either because the worker is cured or, in the worst-case scenario, because the worker dies.

Finally, based on the table of occupational illnesses legally approved and published in the Royal Decree 08/2015, the third variable takes into account six different agents causing occupational illnesses: 1) occupational illnesses caused by chemical agents (e.g., metals, metalloids, halogens, inorganic and organic acids, among others); 2) occupational illnesses caused by physical agents for example noise (equal to or greater than 80 decibels), forced postures and repetitive movements at work, sustained pressure, fatigue, among others); 3) occupational illnesses caused by biological agents (e.g., infections related to hospitalization or health care, infections or parasites transmitted to people by animals or their products and carcasses, infections caused by insects, bacteria and parasites, among others); 4) occupational illnesses caused by inhalation of substances and agents not included in other sections (e.g., dust of silica, aluminum, coal, asbestos, synthesized metals, metallic compounds, among others); 5) occupational skin illnesses caused by substances and agents not included in any of the other sections (e.g., low molecular weight substances below 1,000 daltons including metals, wood dust, pharmaceutical products, plastic chemicals, additives, solvents, preservatives, catalysts, and perfumes; and high molecular weight substances, for over 1,000 daltons, including substances of plant and animal origin, microorganisms and enzymatic substances, animal and/or microorganisms); and 6) occupational illnesses caused by carcinogenic agents (e.g., asbestos, aromatic amines, arsenic and its compounds, benzene, beryllium, bis-(chloro-methyl) ether, cadmium, vinyl chloride monomer, chromium VI, etc.).