Article

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.18845/te.v16i2.6187

Measuring the credibility of consumer-generated media (CGM): a scale to test credibility in the field of tourism.

Medición de la credibilidad de los medios generados por el consumidor (CGM): una escala para probar la credibilidad en el ámbito del turismo

TEC Empresarial, Vol. 16, n°. 2, (May - August, 2022), Pag. 79 - 93, ISSN: 1659-3359

AUTHORS

Ricardo Castano *

Departamento de Gestión de Organizaciones – Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Administrativas - Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Cali, Colombia.

ricardo.castano@javerianacali.edu.co.

![]()

Diana Escandon-Barbosa

Departamento de Gestión de Organizaciones – Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Administrativas - Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Cali, Colombia.

dmescandon@javerianacali.edu.co.

![]()

* Corresponding Author: Ricardo Castano

ABSTRACT

Abstract

This research proposes a scale to measure the credibility of consumer-generated media (CGM). Two studies were carried out: first, a qualitative study based on eleven in-depth interviews with experts in tourism decisions; and second, we ran a quantitative analysis on a sample of 300 frequent users of tourism CGM platforms. The resulting scale, which consists of 4 dimensions and 12 items, is used to measure the credibility of information published in the tourism CGM platforms. The scale was tested for its dimensionality, reliability, and validity; and the results corroborate its accuracy and value as a source of information for travel decision-making. Finally, future lines of research are presented.

Keywords: Tourism, Consumer-Generated Media (CGM), Information Quality, Information Amount, experience, Colombia.

Resumen

Esta investigación propone una escala para medir la credibilidad de los medios generados por el consumidor (CGM). Se realizaron dos estudios: el primero fue un estudio cualitativo basado en once entrevistas en profundidad a expertos en decisiones turísticas y el segundo fue un estudio cuantitativo utilizando una muestra de 300 encuestas a usuarios frecuentes de plataformas CGM de turismo. En consecuencia, se propone una escala compuesta por 4 dimensiones y 12 ítems para medir la credibilidad de la información publicada en las plataformas CGM de turismo como fuente para la toma de decisiones de viaje. La escala se probó en cuanto a su dimensionalidad, confiabilidad y validez. Finalmente, se presenta futuras líneas de investigación.

Palabras clave: Turismo, Medios generados por el consumidor (CGM), calidad de la información, cantidad de información, experiencia, Colombia.

Introduction

1. Introduction

The credibility of consumer-generated media (CGM) indicates the credibility users assign to the messages other people post on websites regarding their experiences with a product, service, or brand. It is difficult to estimate the credibility of the source of information in e-WOM communications given that they are usually written by anonymous sources that are not related to the recipient (Filieri et al., 2015). Existing research that has sought to understand CGM-based traveler behavior has focused on aspects such as participation in online communities (Wang & Fesenmaier, 2004), the implications of CGM on travel decisions (Cox et al., 2009), the various forms of user-generated content (Chen et al., 2014), the perceived usefulness of CGM content (Neijens et al., 2011), the trustworthiness of the CGM source (Filieri et al., 2015), and information and regulatory influence (Book & Tanford, 2020).

While these studies explain traveler behavior in light of the information found on digital platforms, the perception travelers have of the credibility of CGM deserves further attention. This research aims to develop a measurement scale for the perception of the credibility of CGM through the research question: How can the credibility of the information published in CGM be measured? To do so, a scale that takes into account the increasing use of websites to make travel decisions is presented, as travelers require the sources they use to be perceived as credible and trustworthy. (Girish et al., 2021; Book & Tanford, 2020; Filieri et al., 2015; Ayeh, 2015).

The recipient's perception of a digital media message is systematically studied through a consumer-generated media (CGM) credibility scale. This concept of credibility is consistent with the Credibility Theory, which studies the factors associated with the credibility of the news media (Hovland et al., 1953; Sternthal, et al., 1978). Experience, information quality, information amount and reputation of the medium are used as sub-dimensions of the CGM credibility scale.

This article is divided into the following sections: first, a literature review of the main constructs; second, the methodology used in the qualitative and quantitative studies; third, the obtained results; and finally, the academic and practical implications, as well as future research approaches.

2.1 A credibility approach for consumer-generated media (CGM)

CGM are online information sources used by consumers to share information about products, services, and topics with each other (Correia-Loureiro et al., 2020; Litving & Dowling, 2018; Xiang & Gretzel, 2010). The development of the internet and the ability of users to create and publish content has led to active online communities that provide useful information about products and services (Ganzaroli et al., 2017). Social networks are key sources of information that play a leading role in helping travelers decide their travel destinations (Litvin & Dowling, 2016; Xiang & Gretzel, 2010).

The factors associated with users’ acceptance of technologies have enabled improvements in the credibility of CGM, aiding vacation or travel planning (Ayeh, 2015). Credibility has become an effective tool for persuading individuals (Newell & Goldsmith, 2001); greater interaction between the user and the company increases the messages’ credibility and creates a feeling of belonging, therefore generating a better corporate reputation (Barreda et al., 2016; Eberle et al., 2013).

The connection between CGM and credibility is illustrated in the Source Credibility Theory (Hovland et al., 1953), which has been used in marketing and communication research to compare the support and credibility of different media (Johnson & Kaye, 2009; Pornpitakpan, 2004). Lowry et al. (2014) explain that the Source Credibility Theory facilitates the understanding of why some sites are more credible than others and details how the degree of persuasion depends on the credibility of its source.

The Source Credibility Theory has been successfully applied to online communication methods (Jang et al., 2020; Ayeh, 2015; Lowry et al., 2014; Flanagin & Metzger, 2007; Fogg, 2003) to examine the relationship between credibility and information usefulness, information system acceptance, website reliability, perceived experience, and other aspects that may be relevant for travelers who access CGM content. Moreover, various studies have used the Source Credibility Theory to analyze the effects on consumer outcomes, such as their attitude towards a message, purchase intentions, or the adoption of information (Jang et al., 2020; Kim & Kim, 2013; Li, 2013).

To summarize, the credibility of the source positively influences people’s motivation to seek information and entertainment, and their inclination to continue to use these sources, which is why travelers are increasing their use of CGM to share information (Filieri et al., 2015; Hur et al., 2017). The crucial role of online media today requires a conceptualization that accounts for the notion of credibility in CGM, which is provided in this article through the development of a measurement scale based on the principles of the Source Credibility Theory.

2.2 Sub-dimensions of credibility in CGM posted by traveling users

Theorists describe credibility as a multi-dimensional construct (Ohanian, 1990), although single-item measures are treated as one-dimensional (MacKenzie & Lutz, 1989). Therefore, using a reliable and valid scale facilitates standardization and encourages new research (Newell & Goldsmith, 2001).

In order to identify the dimension of credibility, studies on CGM in the area of hospitality and tourism must considered. Given that social networks are the main platforms travelers use to share their experiences online (Xiang & Gretzel, 2010), these considerations are essential for travel planning (Yoo & Gretzel, 2011). Existing research examines the perception of credibility of CGM amongst travelers, as it analyses how the perceived credibility is affected by information valence and source identity in the travel services that are being reviewed in CGM (Kusumasondjaja et al., 2012).

This entails the identification of the role of the following factors perceived by travelers: ease of use, reliability, enjoyment, and integrity. The perceived expertise factor is also considered (Ayeh, 2015) when making travel decisions using reviews from CGM (Ayeh et al., 2013). Additionally, information quality, website quality, satisfaction, and user experience increase the perceived credibility of CGM (Filiery et al., 2015). The source and quality of online reviews, blogs, and texts have a significant effect on the credibility of CGM (Chakraborty & Bhat, 2018) and the influence of brand loyalty is seen in reviews published on CGM platforms (Litvin & Dowling, 2018).

The dimensions and the credibility scales used in previous studies are similar to the methodological design of the scale used in this article. Credibility research has measured and conceptualized the scales according to source credibility, advertising credibility, ad content credibility, and media credibility (Soh et al., 2007). Therefore, the scales used to create the CGM credibility scale for travelers were based on the existing scales of subcategories of source and media credibility; both of these concepts are related to CGM as they all are online information sources that provide user reviews.

According to the procedure carried out in step two of the methodology, the following credibility dimensions were obtained for CGM posted by travelers:

Media Reputation: Blogs where information is posted are considered a form of CGM that can influence a company’s reputation, particularly blogs in which the company’s employees publish information about the business, which increases the number of reviewing users (Agag & El-Masry, 2017; Aggarwal et al., 2012). CGM users search for information on websites with comments from people who have had similar experiences regarding travel and travel-related matters (Kwok et al., 2017). Reputation directly affects the users’ perceived risk of using a hosting service (Sun, 2014).

Information Amount: The amount of information seems to have a significant impact on travelers’ approval of online reviews (Filieri, 2015; Filieri & McLeay, 2014). Travelers need to gather enough information before making decisions. In addition, tourism-related products include different services such as accommodation, transport, restaurants, and entertainment, which makes travel planning complex (Filieri et al., 2015).

Information Quality: People have emotional responses based on the quality of the information they read, which is one of the inputs that enables them to better relate to a brand (Gu et al., 2007; Kim & Johnson, 2016). Furthermore, to enhance the quality of the information, websites should focus on encouraging users who post comments to provide objective and constructive feedback about a product or service (Salehi-Esfahani et al., 2016). If the content is reliable, a user can form a distinct attitude towards the tourism product/service (Sparks et al., 2013).

Experience: The human experience is based on users’ level of satisfaction with the tourist services offered by different companies in the industry. The level of satisfaction serves as an evaluation whereby clients test the services received at the site (Hunt, 1975). Experience includes the paradigms of expectation and reputation, which are manifested in the tourists’ level of satisfaction, specifically in the way it influences the choice of a destination, the consumption of products, and the decision to return to a given destination (Yoon & Uysal, 2005).

Methods

3. Methodology

3.1 Sample and procedure

A scale to measure credibility was developed following the process established by Churchill (1979). The development consisted of four steps: specifying the construct, analyzing the items, data cleansing, and confirming the scale.

The first step entailed conducting a literature review to identify different measures, perspectives, and ideas about the Credibility scale. The selection of articles published in high-impact scientific journals was based on the presentation by Briner and Walshe (2015) in which several articles available on the Web of Science (WoS) were identified. Consequently, the topic of interest was limited to studies published in the main tourism and hospitality magazines (Gursoy & Sandstrom, 2016).

The search yielded 552 articles: 15 on consumer-generated media (CGM), 13 on credibility scales, and 524 on reputation. The 524 reputation articles were filtered by most cited in the field, resulting in 34 articles. The base result was 62 articles that were reviewed in-depth for psychometric scales that measured subjects’ perception of the credibility of the information, thus seeking to obtain valid constructs with which to develop the measurement scale. Then, following the classification proposed by Soh et al. (2007) to measure credibility, scales were selected if they belonged to the categories source credibility or media credibility.

3.2 Experts

An in-depth interview is an information gathering technique based on oral interactions between an interviewer and an interviewee, which enables a dialogue to be built based on a research problem (Bozeman, 2003; Goldman, 1962). According to Churchill (1979), a scale shows a concept that can be compared, and in order to do that, a list composed of elements determined by the literature must be developed. It is then followed by in-depth interviews.

The present research study took this step to increase the validity of the scale. The interviews were conducted in 2018 and ten were selected by intentional open sampling (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003). They were considered saturated after the eleventh interview, when the answers given were found to be comparable to the ten previous interviews. Table 1 shows the item selection process.

|

Number of Reviewers |

Reviewers |

Activity |

Items deleted/ included |

New scale after this step |

Comments or suggestions |

|

Three (3) |

Researchers |

Literature review of the different scales used in other research |

24 items deleted (items with similarities with other dimensions) |

80 items |

The researchers suggest eliminating repetitive items that could confuse a subject’s understanding. (5 items from "celebrity endorsers,” 3 items "source credibility,” 15 items "serv-qual.") Reduced the initial 104 to 80 items |

|

Eleven (11) |

Experts |

Interviews with experts who review the items and determine those that apply to the study. |

64 items (Items were eliminated because they were too similar to other concepts and created problems in their understanding) |

16 items |

Experts suggest items to know CGM credibility. The experts recommended including items for the "Amount of information" dimension. Reduced the initial 80 to 16 items |

3.3 Identified and categorized dimensions

The process of identification and classification of the information was carried out employing a basic thematic analysis, which consisted of an analysis of the content found in traditional and digital media to quantify the number and type of advertisements (Andreú, 2002; Bardin, 1996). The analysis of individual interviews focused on establishing the points of consensus in the participants’ responses. Although this investigation consisted of twelve qualitative reports, it was found that after the ninth report no new relevant information was introduced (Sandelowski, 1995; Sandelowski & Barroso, 2003).

Afterward, the 80 selected items were presented to the interviewees. The experts then indicated which items would allow for a better measurement of the credibility of CGM. The items of a scale can be adjusted to the context of the field of study (Choi et al., 2016). Based on the methodology proposed by Liu et al. (2017), 16 credibility items were obtained, which were identified and categorized into four dimensions: environmental reputation, information quality, information amount, and experience. Each dimension was composed of four items. It is important to highlight that the items regarding information amount were proposed by the experts (Bardin, 1996). Based on their recommendations, only the items they most agreed on were used.

3.4 Questionnaire and CFA

The analysis unit includes users who employ CGM platforms and use the internet to acquire or purchase tourism-related products, hotel reservations, and other services offered on these platforms. Table 2 shows the technical data framework of the study.

|

The population of the investigation |

49,601,593 inhabitants |

|

The geographic scope of the sample |

Colombia cities: Barranquilla, Bogotá, Cali and Medellin |

|

Population size (people who buy online) |

14,880,477 inhabitants |

|

Sample size formula |

|

|

Sample unit |

302 |

|

Sampling process |

Random stratified with assignment |

|

Valid inquests |

300 |

|

Sample error at 95.5% (p= q= 50%) |

+/- 5,68% |

|

Confidence level |

95% |

Based on the results of the qualitative component of this study, a 16-item scale is proposed. This scale is used to measure credibility for users who access CGM. The items are of the reflective type in association with the following dimensions: 1. media reputation, 2. information amount, 3. information quality, and 4. experience. The items included in information amount were the result of the recommendations provided by the experts during the in-depth interviews conducted in the qualitative component of this research.

The results of the confirmatory factor analysis are presented; the number of factors, the level of relationship or independence between them, and the relationship between the factors and the variables are determined (Long, 1983; Stapleton, 1997; Petrick, 2002). The exploratory factor analysis does not provide evidence for the one-dimensionality of the essential measures in the development of the scale (Bush et al., 1990). Therefore, confirmatory factor analysis can be used to group variables into one factor or into the required number of factors (Hair et al., 1999). Table 3 displays the results obtained in the factor analysis.

|

Items Description |

Items |

Item Loading |

T - value |

Reliability SCR AVE |

|

Media Reputation |

||||

|

The comments published on the websites are trustworthy in a purchase decision |

P6_1 |

0,859 |

44,44 |

SCR=0,92 AVE=0,767 |

|

The comments published on the web page are sufficiently reliable |

P6_2 |

0,946 |

64,30 |

|

|

The ease of the communication of the comments published on the web page is convincing |

P6_3 |

0,817 |

36,30 |

|

|

Information Amount |

||||

|

The number of comments posted by other people on the web page is adequate. |

P7_1 |

0,883 |

39,71 |

SCR=0,958 AVE=0,697 |

|

The amount of evidence published by other people is appropriate (for example, photographs) |

P7_2 |

0,842 |

34,36 |

|

|

The amount of detail published by other people on the web page is sufficient |

P7_3 |

0,776 |

27,69 |

|

|

Information Quality |

||||

|

The quality of the comments published by other people is relevant |

P8_1 |

0,705 |

20,44 |

SCR=0,85 AVE=0,692 |

|

The level of detail of the comments published by other people is convincing |

P8_2 |

0,869 |

32,22 |

|

|

The age of the information published by other people is important to measure the quality of the information |

P8_3 |

0,825 |

28,52 |

|

|

Experience |

||||

|

The service of the staff at the place visited was pleasant, and it was evidenced in the review comments on the web page |

P9_2 |

0,694 |

17,83 |

SCR=0,91 AVE=0,637 |

|

The location of the visited place was pleasant and was in accordance with the comments on the web page |

P9_3 |

0,864 |

25,05 |

|

|

The comments published on the web page met the expectations regarding the place visited |

P9_4 |

0,684 |

17,18 |

|

|

RMSEA |

0.064 |

|||

|

CFI |

0,968 |

|||

|

TLI |

0,956 |

|||

It can be observed that the comparative fit index (CFI) indicates a good fit to the model at 0.968, higher than the threshold value of 0.95 (Bentler & Bonett, 1980). The Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) compares the adjustment by degrees of freedom of the proposed and unaccepted models; this index showed a value of 0.956, which indicates a good fit, as it is higher than 0.9 (Kohli et al., 1993). The fit of the model in research related to the development of scales is divided into three steps: (a) Analysis of the standardized parameters and their standard errors (Brown, 2015; Byrne, 2001); (b) an index adjustment (Brown, 2015), and (c) verifying that the absolute value of the standardized residual covariance is greater than 2.0.

Three model fitting iterations were carried out to achieve the final model. Items were eliminated as a consequence of their relatively low loads (.01). Through the covariance of the errors, it was identified that the data fit the model (Byrne, 2001). Three of the factors showed significant covariance (<.05).

3.5 Scale Validation

The validation in the second group sought to meet three objectives: test the scale with a larger sample of credibility of CGM; validate the structure of all factors in a more general population; and demonstrate convergence, concurrence, discrimination, and validity in the final scale (Table 4 presents the covariance results).

|

Pair |

Estimate |

SE |

P-value |

|

MR …….AI |

0.13 |

0,06 |

0.06 |

|

MR…….QI |

0,14 |

0,09 |

0,03 |

|

MR…….E |

0,16 |

0,06 |

0,02 |

|

AI……...QI |

0,34 |

0,07 |

0,00 |

|

AI……...E |

0,51 |

0,07 |

0,00 |

|

QI……...E |

0,45 |

0,08 |

0,00 |

3.6 Data collection and sampling

The elements of the previous final model were tested with all the elements of comprehensibility of the validation study to analyze if the factor showed different results with a sample of non-students. A total of 22 items were tested. A second-order model was tested to consider the credibility of CGM. The theory represented by the subdimensions of the four constructs was applied to ensure content validity. It was suggested that the items related to the IQ and IA scales be eliminated due to their high standardized residual covariance. An even weaker model was shown in the second 20-item model. Due to poor standardized residual covariance values for IQ5, IQ6, and IA6, which were reported by MI statistics, these elements were eliminated.

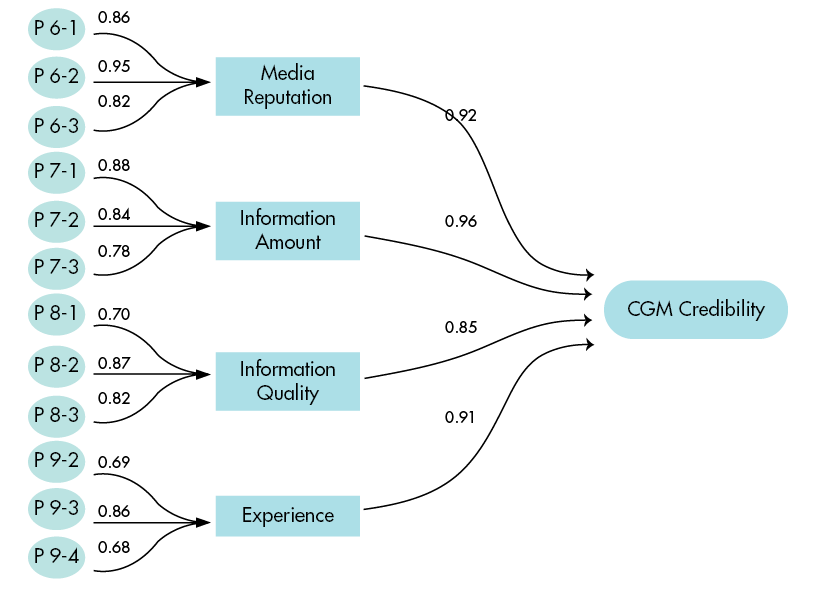

Furthermore, the first item related to IQ was defined in two different factors and was therefore eliminated. The items IA2, IA3, and MR4 were leading to an overemphasis of that consideration. E4 was removed from the scale due to the wording of the items E1 and E3. The element and factor loads are shown in Figure 1. All the item loads are significant (p <0.001) above 0.5. Moreover, the four factors provided loads (p <.001) in the higher order of the CGM credibility construct. Information amount had a load of 0.96, experience of 0.91, information quality of 0.85, and media reputation of 0.92. With CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.70, and SRMR = 0.06, the general fit of the model was good (Brown, 2015). Information quality in the CGM Credibility scale was high (α = .88); it would not be possible to improve Information quality by eliminating elements. In the CGM Credibility scale, Information quality had a CR of .94 (Raykov, 1997). It seems that this 16-item scale is a good representation of the credibility of CGM.

3.7 Discriminant Validity

The discriminant legitimacy confirms that the value "1" was not within the confidence intervals for each pair of configurations; therefore, the confidence intervals are indifferent (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). Additionally, in each scale, the mean variance extracted was greater than the variance shared with the eliminated structure, confirming the precision of the identification.

In Table 5, a summary of the items for the constructs used in the research is presented. This provides an overview of the interrelations between the items of the four constructs. The correlations are also included.

|

Scale |

Dimension |

Items |

|

Celebrity Endorsers Credibility Scale Media Credibility (Soh et al., 2007) Source Credibility (Filieri, 2015) |

Media reputation |

1. The published comments on the web pages are honest for a purchase decision 2. The published comments on the web pages are sufficiently reliable 3. The ease of communication is convincing in published comments on a web page 4. Web pages that have a higher number of comments from users are extremely credible |

|

Result of the qualitative component |

Information amount |

5. The number of comments posted by other people on the web pages is adequate 6. The amount of evidence published by other people is appropriate (for example, photographs) 7. The amount of details published by other people on the web pages is sufficient 8. The volume of information that is published by other people on the web pages is useful |

|

Advertiser credibility Media credibility (Soh et al., 2007) Source Credibility (Filieri, 2015) |

Information quality |

9. The quality of the published comments by other people is relevant 10. The level of detail of the published comments by other people is convincing 11. The age of the published information by other people is important to measure the quality of the information 12. The accuracy of the published information in the comments of other people is significant |

|

SERVQUAL |

Experience |

13. The cleanliness of the visited place was satisfactory and in accordance with the comments published on the web page 14. The service of the staff in the visited place was pleasant, and it was evidenced in the reviewed comments on the web page 15. The location of the visited place was pleasant and was in accordance with the comments on the web page 16. The comments published on the web page met the expectations regarding the place visited |

3.8 Convergent Validity

The OLS method enables the estimation of the parameters in a linear regression model. Mackenzie et al. (2011) state that convergence is used to analyze the relationship between constructs that are meant to be in a similar nomological network. Therefore, an all-concept regression method was developed to verify CGM Credibility relationships within their nomological connections. Each factor has a positive relationship with CGM Credibility, and the regression confirms this contribution (see Figure 1).

3.9 Concurrent Validity

Concurrent validity of the CGM Credibility scale was performed by showing the relationship between the developed construct and the outcome variable, such as commitment (Cheng, 1990), which is a construct used in the fields of business and tourism. If tourists perceive CGM as credible, it can influence their decision-making process and it will increase the likelihood of them booking hotels recommended on the platform, thus enhancing their engagement (Tsai & Men, 2013). A linear regression model using CGM Credibility as the dependent variable and engagement as the independent variable was developed and confirmed (R2 = .13, β = .31, B = .16, SE = 0.02, t(1) = 3.62, p < .001).

Figure 1: Model of CGM Credibility |

|

Concluding

4. Discussion and implications

The results of this research have several implications for theory and practice. The novelty of this research stems from the proposal of a scale that measures the credibility of the information published in CGM in the field of tourism, as there is a need to understand the perceived credibility the consumers of tourism-related services assign to the information published in CGM platforms when making travel decisions (Girish et al., 2021; Book & Tanford, 2020; Filieri et al., 2015; Ayeh, 2015). This study was based on the proposal of Soh et al (2007) to create a "CGM Credibility Scale" that is developed and conceived taking into account the idea that CGM is a multidimensional concept that could be measured using four factors: "media reputation”, "information quality", "experience" and "information amount". The last factor was the result of the qualitative component of this research. Tests were carried out to ensure construct reliability and validity for this scale. Five steps were taken: a literature review, followed by in-depth interviews and two validations with different samples.

The CGM Credibility Scale could be expanded on in future research using new factors. This research adds to existing studies that suggest that CGM users can search for information online through comments from other users who have shared positive and negative information regarding their travel experiences (Kwok et al., 2017). Moreover, the results coincide with the statements of Sun (2014) and Liu and Park (2015), who argued that the reputation of a travel company can be influenced by the users’ perceived risk based on the information published in CGM.

Additionally, this study has practical implications. It not only helps companies to measure the credibility users assign to CGM published on the internet, but also offers contributions that can be considered for the design and implementation of corporate marketing strategies, which is congruent with the findings of Levy et al. (2013). Moreover, hotels should focus on the comments that are published on their websites to improve their interactions with customers, thus obtaining a better financial performance (Xie et al., 2017).

Finally, with the companies' knowledge about the credibility users assign to CGM, they could try to increase the perceived usefulness of CGM by improving their ease of use (Ayeh, 2015). Therefore, the proposed credibility scale can assist designers and administrators of CGM in the design of social media marketing strategies.

This study has several implications and considers some limitations. First, the fieldwork of this research was conducted in Colombia, which has a wide and diverse spectrum of cultural and behavioral traits that affect how people use CGM to make travel planning decisions. Further empirical studies of the credibility of CGM should be carried out in other countries. Second, it is necessary to improve the suggested scale so that it can be used in new research studies. Thus, we recommend that further research be conducted to validate the model and to improve the items of the scale. To summarize, additional studies are needed to provide a longitudinal analysis of the credibility of CGM in all its dimensions (media reputation, information amount, information quality, and users’ experience).

References

References

Agag, G. M., & El-Masry, A. A. (2017). Why do consumers trust online travel websites? Drivers and outcomes of consumer trust toward online travel websites. Journal of Travel Research, 56(3), 347-369. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516643185

Aggarwal, R., Gopal, R., Sankaranarayanan, R. & Singh, P. V. (2012). Blog, Blogger, and the firm: Can negative employee posts lead to positive outcomes? Information Systems Research, 23(2), 306–322. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1110.0360

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

Andreú, J. (2002). Las técnicas de Análisis de Contenido: una revisión actualizada. Fundación Centro de Estudios Andaluces, 1–34. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_cdmu.2013.v24.46279

Ayeh, J. K.; Au, N. & Law, R. (2013). Predicting the intention to use consumer-generated media for travel planning. Tourism Management, 35, 132-143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.06.010

Ayeh, J. K. (2015). Travelers’ acceptance of consumer-generated media: An integrated model of technology acceptance and source credibility theories. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 173-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.049

Bardin, L. (1996). Análisis de contenido. Madrid. España: Akal Editores.

Barreda, A. A., Bilgihan, A., Nusair, K., & Okumus, F. (2016). Online branding: Development of hotel branding through interactivity theory. Tourism Management, 57, 180-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.06.007

Bentler, P. M. & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

Bozeman, B. (2003). Handbook of Interview Research: Context and Method-Jaber Gubrium, James Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of Interview Research: Context and Method, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, 2002, 981 pages. Evaluation and Program Planning, 1(26), 37-39.

Briner, R. B. & Walshe, N. D. (2015). An evidence-based approach to improving the quality of resource-oriented well-being interventions at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(3), 563-586. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12133

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford publications.

Bush, R. P., Ortinau, D. J., Bush, A. J., & Hair Jr, J. F. (1990). Developing A Behavior Based Scale to Assess Retail Salesper. Journal of Retailing, 66(1), 119.

Book, Laura A.; Tanford, Sarah (2020). Measuring social influence from online traveler reviews. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 3(1), 54-72. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-06-2019-0080

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. International Journal of Testing, 1(1), 55-86. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327574IJT0101_4

Chakraborty, U., & Bhat, S. (2018). Credibility of online reviews and its impact on brand image, Management Research Review, 41(1), 148-164. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-06-2017-0173

Chen, Y.-C., Shang, R.-A., & Li, M.-J. (2014). The effects of perceived relevance of travel blogs’ content on the behavioral intention to visit a tourist destination. Computers in Human Behavior, 30, 787–799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.05.019

Cheng, Y. C. (1990). The Relationship of Job Attitudes and Organizational Commitment to Different Aspects of Organizational Environment. ERIC Document Reproduction Service No ED 318-779

Choi, M., Law, R., & Heo, C. Y. (2016). Shopping destinations and trust–tourist attitudes: Scale development and validation. Tourism Management, 54, 490-501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.01.005

Churchill, G. A. (1979). A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377901600110

Correia-Loureiro, S. M., Guerreiro, J., & Ali, F. (2020). 20 years of research on virtual reality and augmented reality in tourism context: A text-mining approach. Tourism management, 77, 104028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104028

Cox, C., Burgess, S., Sellitto, C., & Buultjens, J. (2009). The role of user-generated content in tourists’ travel planning behaviour. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18, 743–764. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368620903235753

Eberle, D.; Berens, G. & Li, T. (2013). The Impact of Interactive Corporate Social Responsibility Communication on Corporate Reputation. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(4), 731–746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1957-y

Filieri, R. (2015). What makes online reviews helpful? A diagnosticity-adoption framework to explain informational and normative influences in e-WOM. Journal of Business Research, 68 (6). pp. 1261-1270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.11.006

Filieri, R., Alguezaui, S. & McLeay, F. (2015). Why do travelers trust TripAdvisor? Antecedents of trust towards consumer-generated media and its influence on recommendation adoption and word of mouth. Tourism Management, 51, 174-185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.05.007

Filieri, R. & McLeay, F. (2014). E-WOM and Accommodation: An Analysis of the Factors That Influence Travelers’ Adoption of Information from Online Reviews. Journal of Travel Research, 53(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513481274

Flanagin, A. J., & Metzger, M. J. (2007). The role of site features, user attributes, and information verification behaviors on the perceived credibility of web-based information. New media & society, 9(2), 319-342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444807075015

Fogg, B. J. (2003, April). Prominence-interpretation theory: Explaining how people assess credibility online. In CHI'03 extended abstracts on human factors in computing systems (pp. 722-723). https://doi.org/10.1145/765891.765951

Ganzaroli, A.; De Noni, I. & Van Baalen, P. (2017). Vicious advice: Analyzing the impact of TripAdvisor on the quality of restaurants as part of the cultural heritage of Venice. Tourism Management, 61, 501-510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.03.019

Girish, V. G., Park, E., & Lee, C. K. (2021). Testing the influence of destination source credibility, destination image, and destination fascination on the decision-making process: Case of the Cayman Islands. International Journal of Tourism Research, 23(4), 569-580. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2427

Goldman, A. E. (1962). The group depth interview. Journal of marketing, 26(3), 61-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224296202600313

Gu, B., Konana, P.; Rajagopalan, B. & Chen, H. W. M. (2007). Competition among virtual communities and user valuation: The case of investing-related communities. Information Systems Research, 18(1), 68-85. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1070.0114

Gursoy, D. & Sandstrom, J. K. (2016). An Updated Ranking of Hospitality and Tourism Journals. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 40(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348014538054

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1999). Análisis multivariante (Vol. 491). Madrid: Prentice Hall.

Hovland, C. I., Janis, I. L., & Kelley, H. H. (1953). Communication and persuasion. Yale University Press.

Hunt, J. D. (1975). Image as a factor in tourism development. Journal of travel research, 13(3), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728757501300301

Hur, K.; Kim, T. T., Karatepe, O. M. & Lee, G. (2017). An exploration of the factors influencing social media continuance usage and information sharing intentions among Korean travelers. Tourism Management, 63, 170-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.06.013

Johnson, T. J., & Kaye, B. K. (2009). In blog we trust? Deciphering credibility of components of the internet among politically interested internet users. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(1), 175-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.08.004

Jang, W. E., Jihoon (Jay) Kim, Soojin Kim & Jung Won Chun (2020). The role of engagement in travel influencer marketing: the perspectives of dual process theory and the source credibility model, Current Issues in Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1845126

Kim, J., Ahn, K. & Chung, N. (2013). Examining the factors affecting perceived enjoyment and usage intention of ubiquitous tour information services: A service quality perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 18(6), 598-617. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2012.695282

Kim, S.-B., & Kim, D. Y. (2013). The effects of message framing and source credibility on green messages in hotels. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965513503400

Kim, A. J. & Johnson, K. K. (2016). Power of consumers using social media: Examining the influences of brand-related user-generated content on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 98-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.047

Kohli, A. K., Jaworski, B. J. & Kumar, A. (1993). MARKOR: A Measure of Market Orientation. Journal of Marketing Research, 30(4), 467. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379303000406

Kusumasondjaja, S., Shanka, T., Marchegiani, C. (2012). Credibility of online reviews and initial trust The roles of reviewer’s identity and review valence. Journal Of Vacation Marketing 18(3):185-195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766712449365

Kwok, L., Xie, K. L., & Richards, T. (2017). Thematic framework of online review research: A systematic analysis of contemporary literature on seven major hospitality and tourism journals. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(1), 307-354. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-11-2015-0664

Levy, S. E.; Duan, W. & Boo, S. (2013). An analysis of one-star online reviews and responses in the Washington, DC, lodging market. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(1), 49-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965512464513

Li, C.-Y. (2013). Persuasive messages on information system acceptance: A theoretical extension of elaboration likelihood model and social influence theory. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(1), 264–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.09.003

Litvin, S. W. & Dowling, K. M. (2016). TripAdvisor and hotel consumer brand loyalty. Current Issues in Tourism, 0(0), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1265488

Litvin, S. W., & Dowling, K. M. (2018). TripAdvisor and hotel consumer brand loyalty. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(8), 842-846. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1265488

Liu, Z. & Park, S. (2015). What makes a useful online review? Implication for travel product websites. Tourism Management, 47, 140-151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.09.020

Liu, C. R.; Wang, Y. C., Huang, W. S. & Chen, S. P. (2017). Destination fascination: Conceptualization and scale development. Tourism Management, 63, 255-267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.06.023

Long, J. Scott (1983). Confirmatory Factor Analysis: A Preface to LISREL, Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, Newbury Park & London, Sage.

Lowry, P.V., Wilson, D.W, & Haig, W. L. (2014). A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words: Source Credibility Theory Applied to Logo and Website Design for Heightened Credibility and Consumer Trust, International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 30:1, 63-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2013.839899

MacKenzie, S. B. & Lutz, R. J. (1989). An Empirical Examination of the Structural Antecedents of Attitude toward the Ad in an Advertising Pretesting Context. Journal of Marketing, 53(2), 48. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298905300204

MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2011). Construct measurement and validation procedures in MIS and behavioral research: Integrating new and existing techniques. MIS quarterly, 293-334.

Neijens, P. C., Bronner, F., & De Ridder, J. A. (2011). Highly recommended! The content characteristics and perceived usefulness of online consumer reviews. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 17(1),19-38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2011.01551.x

Newell, S. J. & Goldsmith, R. E. (2001). The development of a scale to measure perceived corporate credibility. Journal of Business Research, 52(3), 235-247. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(99)00104-6

Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers' perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of advertising, 19(3), 39-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673191

Petrick, J. F. (2002). Development of a multi-dimensional scale for measuring the perceived value of a service. Journal of leisure research, 34(2), 119-134. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2002.11949965

Pornpitakpan, C. (2004). The persuasiveness of source credibility: A critical review of five decades' evidence. Journal of applied social psychology, 34(2), 243-281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02547.x

Raykov, T. (1997). Estimation of composite reliability for congeneric measures. Applied Psychological Measurement, 21(2), 173-184. https://doi.org/10.1177/01466216970212006

Rauch, D. A., Collins, M. D., Nale, R. D. & Barr, P. B. (2015). Measuring service quality in mid-scale hotels. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(1), 87–106. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-06-2013-0254

Salehi-Esfahani, S., Ravichandran, S., Israeli, A., & Bolden III, E. (2016). Investigating information adoption tendencies based on restaurants’ user-generated content utilizing a modified information adoption model. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 25(8), 925-953. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2016.1171190

Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in nursing & health, 18(2), 179-183. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770180211

Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2003). Classifying the findings in qualitative studies. Qualitative health research, 13(7), 905-923. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732303253488

Soh, H., Reid, L. N. & King, K. W. (2007). Trust in different advertising media. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 84(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900708400304

Sparks, B. A., Perkins, H. E. y Buckley, R. (2013). Online travel reviews as persuasive communication: The effects of content type, source, and certification logos on consumer behavior. Tourism Management, 39, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.03.007

Stapleton, Connie D. (1997). Basic Concepts and Procedures of Confirmatory Factor Analysis. http://mirror.eschina.bnu.edu.cn/Mirror1/accesseric/ericae.net/ft/tamu/Cfa.html

Sternthal, B., Dholakia, R., & Leavitt, C. (1978). The persuasive effect of source credibility: Tests of cognitive response. Journal of Consumer research, 4(4), 252-260. https://doi.org/10.1086/208704

Sun, J. (2014). How risky are services? An empirical investigation on the antecedents and consequences of perceived risk for hotel service. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 37, 171-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.11.008

Tsai, W. H. S., & Men, L. R. (2013). Motivations and antecedents of consumer engagement with brand pages on social networking sites. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 13(2), 76-87. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2013.826549

Wang, Y., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2004). Towards understanding members’ general participation in and active contribution to an online travel community. Tourism management, 25(6), 709-722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.09.011

Xiang, Z. & Gretzel, U. (2010). Role of Social Media in Online Travel Information Search. Tourism Management, 31 (2): 179–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.02.016

Xie, K. L., So, K. K. F. & Wang, W. (2017). Joint effects of management responses and online reviews on hotel financial performance: A data-analytics approach. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 62, 101-110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.12.004

Yoon, Y., & Uysal, M. (2005). An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: a structural model. Tourism Management, 26(1), 45-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.08.016.