Article

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.18845/te.v15i1.5399

NEW VENTURE CREATION: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF ASSOCIATED LITERATURE

CREACIÓN DE NUEVAS EMPRESAS: UNA REVISIÓN SISTEMÁTICA DE LA LITERATURA

TEC Empresarial, Vol. 15, n°. 1, (January - April, 2022), Pag. 56 - 79, ISSN: 1659-3359

AUTHORS

Colin Donaldson

Centro Universitario EDEM, Valencia,

Spain.

cdonaldson@edem.es.

![]()

Guillermo Mateu

CEREN, EA 7477, Burgundy School

of Business, Université Bourgogne

Franche-Comté, France & Centro

Universitario EDEM, Valencia, Spain.

guillermo.mateu@bsb-education.com.

![]()

ABSTRACT

Abstract

New venture creation is an integral facet of entrepreneurship and as consequence has been subject to increased research attention within extant literature. Although momentum has been gained in search of explicating this broad and diverse phenomenon there is still great potential to further our understanding. Progress in expanding knowledge will be most effective if we are able to constructively build upon explicitly recognised common foci that can serve as a foundation to cooperative contribution. The current article has the objective of providing an up-to-date thematic overview via systematic means of the main research interests that are being attended to within the new venture creation domain. The study is based on a comprehensive search of the SCOPUS database up until, and including, the year 2017. Thus, there is the useful and original provision of a parsimonious overview of the many heterogenous factors implicated within the process. Citation analysis is used as a framework to distinguish influential publications and their interconnections, with intellectual foundations and theoretical underpinnings driving research presented. A key implication of the work is the provision of a classification of key trending themes based on four priority constructs that can inspire new research avenues and greater collaboration in future investigative efforts.

Keywords: New venture creation; systematic literature review; citation analysis; thematic categories.

Resumen

La creación de nuevas empresas es una faceta integral del emprendimiento y, como consecuencia, ha sido objeto de una mayor atención de investigación dentro de la literatura existente. Aunque se ha ganado impulso en busca de explicar este fenómeno amplio y diverso, existe un gran potencial para ampliar nuestra comprensión. El progreso en la expansión del conocimiento será más efectivo si somos capaces de construir de manera constructiva a partir de focos comunes explícitamente reconocidos que puedan servir como base para una contribución cooperativa. El presente artículo busca proporcionar una visión general temática actualizada a través de medios sistemáticos de los principales intereses de investigación que se están atendiendo dentro del nuevo dominio de creación de empresas. El estudio se basa en una búsqueda exhaustiva de la base de datos SCOPUS hasta el año 2017 inclusive. Por lo tanto, existe la provisión de una visión general parsimoniosa de aquellos factores, a veces heterogéneos, considerados más importantes para el proceso. El análisis de citas se utiliza como marco para distinguir las publicaciones influyentes y sus interconexiones, con fundamentos intelectuales y fundamentos teóricos que impulsan la investigación presentada. Una implicación clave del trabajo es la provisión de una clasificación de temas de tendencia clave basada en cuatro constructos prioritarios que pueden inspirar nuevas vías de investigación y una mayor colaboración en los esfuerzos de investigación futuros.

Palabras clave: Creación de nuevas empresas; revisión de literatura sitemática; análisis de citas; categorías temáticas.

Introduction

INTRODUCTION

Entrepreneurship is an exciting, rapidly evolving and highly influential discipline. It has duly assumed an unequivocal responsibility towards the positive advancement of socioeconomic conditions. Heavily embraced by many academics, governing officials, policymakers, and general practitioners alike, they remain attentive towards its axiomatic impact upon many of the significant contributors to economic and social prosperity (Carree & Thurik, 2005; Fitzsimmons & Douglas, 2005). To negate such critical influence would create opportunistic costs that have the potential to stump any economic dynamism and progression, thus in-so-doing, severely limit capacity for growth (Audretsch et al., 2001). Hence a desire, or for want of being more forthright, a necessity exists to further decompose and gain knowledge surrounding a multi-faceted and differentiated concept that has the ability to create new jobs, improve fiscal health, generate wealth, and better societies.

Associated literature has indulged this manner of thinking. It has progressed from relatively static theoretical hypothesising that sought to identify the elusive blueprint for the archetypical entrepreneur towards the more contemporary interpretation of entrepreneurship as a dynamic and socially situated process. Different effects and outcomes manifest dependent upon interactions between numerous internal and external system variants. One of the most central and fundamental sub-components to this process is the pathway leading to the creation of new ventures (Brush et al., 2008; Omrane & Fayolle, 2011).

Although significant progress has been achieved in attending to new venture creation (NVC), there is still great capacity to accumulate and generate further knowledge (Reynolds, 2017). The most notable source comes from its visible genetic heterogeneity. Interest is not uniquely associated with the entrepreneurship domain per se but instead has featured prominently within many of the preceding organisational and strategic management journals. A large number of these have afforded useful theoretical stage, lifestyle, path dependent, or sequential models (e.g. Gartner, 1985; Kazanjian, 1988; Moore, 1986; Webster, 1976) all serving as localised reference points.

Early studies in search of explanations merely touched upon peripheral elements. A number of diverse and idiosyncratic research approaches were implemented reflective of discipline interests, be them entrepreneurial, organisational, population-based, or from a more macroeconomic perspective. For instance, many from within the industrial organisation field elected to examine the contextual influence on creation through market entry. Others focused on ex-post recollections of ventures that had achieved success. Finally, researchers have delved into self-employment data under the premise that this is indicative of entrepreneurially-based behaviours. The research has become synonymous with its challenging nature. This is especially true in regard to the myriad of variants that present themselves due to these distinct approaches adopted. As consequence, the body of scholarship that exists can prove to be a somewhat daunting prospect for various stakeholders, especially new inhabitants of the research arena.

Thus, it appears that a beneficial trajectory from such a strong foundation, and in search of coherency, may well be the provision of a systematic outlook based on influential contributions and the main themes emanating from these. What follows is a potential to draw together disperse research interests into a clear categorical representation. A systematic approach affords inherent advantages through increasing validity via a clear portrayal of methodological steps taken (Denyer & Neely, 2004) and is much more rigourous due to the linkages that can be made between the evidence captured. It is a worthy undertaking as it allows us to alleviate the somewhat limited and burdensome traditional practices entrenched in entrepreneurship studies that have the potential to restrict both scope and depth of study (Fetscherin & Henrich, 2015)

Accordingly, to the current authors´ better knowledge they have yet to encounter a systematic review underpinned by a citation analysis procedure that deals specifically with a revision of the literature surrounding the concept of NVCa1. This is quite surprising given the impact that this method can exert towards the generation of holistic overviews of complex topics. Therefore, the present paper is accompanied with the objective of abridging this perceived shortcoming by building upon prior industrious insight and providing an up-to-date classification of the topical themes under study2. A clear contribution is made towards the search for a broad, parsimonious, and variant spanning conceptualization of the NVC domain. Consequently, there is the provision of a useful overview of the current state-of-play in regard to research factors of interest and the main themes emanating therafter. Through such endeavour the scholarly advocated development of a coherent understanding of the multifarious NVC process is enacted (Wright & Marlow, 2012, Shane & Venkataraman, 2000).

Methods

METHODOLOGY

NVC literature, given its heterogenous and fragmented composition (Gartner, 2001), by necessity requires a robust and systematic procedure that can afford an analytical framework that is not only replicable but so too transparent (Armitage & Keeble-Allen, 2008). With this in mind and for greater clarity, it is beneficial to firstly set clear conceptual boundaries regarding the topic under study (Denyer & Tranfield, 2009). The definition used for the explanandum in the current context is deliberately encompassing in nature with ambition to amass the assorted fragments of associated literature (see Davidsson´s (2016) portrayal of levels of entrepreneurial analysis for the guiding framework that allowed boundaries to be set).

Accordingly, what transpires is the notion that NVC is both a composite of process, and feature. In other words, it operates and can be studied across multiple levels, but ultimately involves the conceivement, enactment, and start of a new organisation (Forbes, 1999). This unfolds under dynamic and evolving conditions. It embraces preand post-entry into the firm creation process alongside transition from start up to new firm (Reynolds, 2017). Thus, formation of a new entity, the multidimensional nature of such formation, and the contextual influencers (Gartner, 1985), are all contemplated. Consequently, business formation may find genesis in a number of locations and forms, for example, from within or outside existing organisations, it can also serve as auxiliary to opportunities that are either effectuated or identified, and finally it may occur across various levels (individual, team, firm or aggregate).

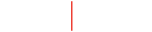

In compliance with an emphasis towards transparency the current review employed a number of distinctive and overt methodological measures (an overview is provided in Figure 1 and the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the appendix). Firstly, only academic journal articles were considered in the accumulated dataset and therefore other publication outlets such as books, book chapters and conference papers etc. were occluded. Through this selection criteria, the present work is in accordance with previous precedents observed within forgone reviews (e.g. Donaldson, 2019; Liñan & Fayolle, 2015; Rhaiem & Amara, 2019). This ensured that the information provided was validated, with peer review acting as a neat proxy for quality increasing its credibility and usefulness (Podsakoff et al., 2005).

Figure 1. Systematic literature review: process implemented |

|

Secondly, a systematic search of the electronic SCOPUS database was enacted. The selection of this particular database was based upon the accepted extensiveness of journal coverage. The search criteria was composed of the keywords and Boolean operators of “New Venture*” AND “Creation*” AND “Process*”, with these words being deemed suffice to gain a broad coverage of the focal theme under examination. From this, a total of 400 journal articles were extracted. The search was further restricted by subject matter to include those areas associated to the business and entrepreneurship disciplines (i.e. Business Management and Accounting; Economics, Econometrics and Finance; Social Sciences) resulting in 215 articles.

After having reviewed the titles and abstracts of each article, further depurification, via means of source, to include those journals perceived to be most allied to both business and entrepreneurship (i.e. those that place explicit interest towards business creation and surrounding issues in their relevancy statements to potential authors) was employed, underpinning an aim to explore and scrutinise articles that are highly concentrated and pertinent. With this source criteria in combination with the construct criteria of duplication, language of text (non-English) and irrelevancy (outside set conceptual boundaries) an additional 60 publications were removed. Thus, a resultant 155 articles composed the final dataset for study.

Next, in order to ensure that the domain was presented in a clear, coherent, and detailed fashion citation analysis was adopted (Gundolf & Filser, 2013). This was implemented under the premise that citation frequency represents a strong portrayal of the importance of a given work and the linkages between research and conceptual adoption in the field (Garfield, 1979; Kraus et al., 2012). Having conformed to the aforementioned source and construct criterion, citation frequency was determined as those articles that had received the greatest number of citations within the accumulated dataset´s own reference base. These were therefore accepted to hold greater importance through exerting an increased significance upon the topic of study. This entailed the exportation of reference lists followed by a duplication search of authors and articles to determine overall total citations.

Subsequently, 23 citations were identified due to their prominence within the dataset and of these 23, three were later discarded as they were not academic articles leaving 20 highly influential papers. In order for solid theory to be built it is imperative that the most salient terms and conceptual ideas associated with a phenomenon, and the relationships and interactions between these thereafter, are uncovered. To account for this, the influential articles were catalogued into groupings corresponding to content which allowed emanating trends to be established. This meant that they could be subsequently allocated into clusters based upon focal topics which in this instance were extricated based upon recurring themes by the authors and comprised of four key thematic priority constructs (Sociological, Resources, Cognition and Process). The final step, was then to classify the accumulated dataset into the consonant cluster analysing and interpreting each in relation to thematic content.

Results

RESULTS

MOST INFLUENTIAL ARTICLES

It was important to determine those articles within the dataset that had received the most number of citations as this provided the foundation upon which cluster development could occur. Each of the 20 key articles were analysed through the examination of their structural properties and content. This permitted the identification of each publication´s level of significance within the research discipline. From this, the four priority level categories of papers could be generated. Table 1 affords a visual representation of these priority groupings detailing the number of citations received, year of publication, and the journal source.

Tabla 1. Top-20 most frequently cited references

| Autor | Yer | Title | Citations | Category | Journal of Publicationª |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granovetter, M.S. | 1985 | Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness | 15 | Sociological | AJOS |

| Granovetter, M.S. | 1973 | The strength of weak ties | 12 | Sociological | AJOS |

| Eisenhardt, K.M.* | 1989 | Building Theories from Case Study Research | 19 | Process | AOMR |

| Katz, J., and Gartner, W.B. | 1988 | Properties of Emerging Organizations | 17 | Process | AOMR |

| Carter, N.M, Gartner, W.B., & Reynolds, P.D. | 1996 | Exploring start-up event sequences | 19 | Process | JOBV |

| Bhave, | 1994 | A process model of entrepreneurial venture creation | 15 | Process | JOBV |

| Gartner, W.B. | 1985 | A conceptual framework for describing the phenomenon of new venture creation | 13 | Process | AOMR |

| Delmar, F., & Shane, S. | 2003 | Does business planning facilitate the development of new ventures? | 13 | Process | SMJ |

| Baron, R.A. | 1998 | Cognitive mechanisms in entrepreneurship: Why and when enterpreneurs think differently than other people | 9 | Cognition | JOBV |

| Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. | 2000 | The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research | 41 | Cognition | AOMR |

| Sarasvathy, S.D. | 2001 | Causation and Effectuation: Toward a Theoretical Shift from Economic Inevitability to Entrepreneurial Contingency | 20 | Cognition | AOMR |

| Krueger, N.F., Reilly, M.D., & Carsrud, A.L. | 2000 | Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions | 19 | Cognition | JOBV |

| Ardichvili, A., Cardozo, R., & Ray, S. | 2003 | A Theory of Entrepreneurial Opportunity Identification and Development | 16 | Cognition | JOBV |

| Bird, B. | 1988 | Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention | 12 | Cognition | AOMR |

| Busenitz, L.W., & Barney, J. | 1997 | Differences Between Entrepreneurs and Managers in Large Organizations: Biases and Heuristics in Strategic Decision-Making | 9 | Cognition | JOBV |

| Lumpkin, G.T., & Dess, C.G. | 1996 | Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance | 10 | Cognition | AOMR |

| McMullen, J.S., & Shepherd, D.A. | 2006 | Entrepreneurial Action and The Role of Uncertainty in The Theory Of The Entrepreneur | 13 | Cognition | AOMR |

| Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. | 2003 | The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs | 27 | Resource | JOBV |

| Shane, S. | 2000 | Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities | 19 | Resource | OS |

| Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. | 1998 | Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage | 12 | Resource | Resource |

ª AOMR (9 papers) Academy of Management Review; AMJOS (2 papers) American Journal of Sociology; JOBV (7 papers) Journal of Business Venturing; SMJ (1 paper) Strategic Management Journal; OS (1paper) Organizational Science *Categorised based upon influence upon the development of theory related to the process of new venture creation.

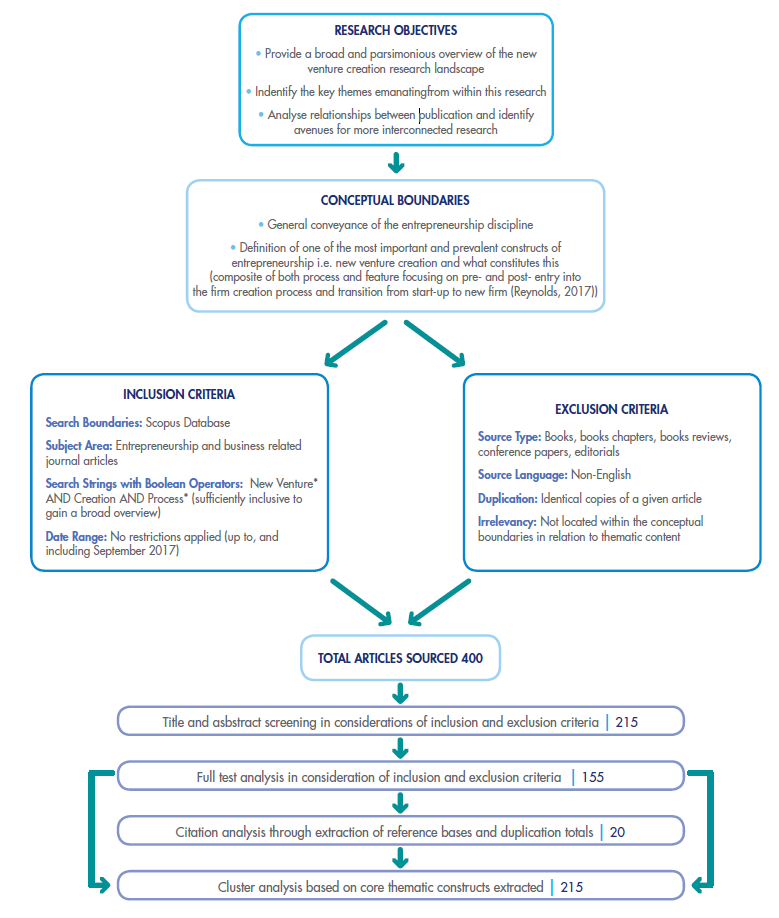

Notably, over half (60%) of these influential articles were published before the year 2000 in management and organisation related journals with a cluster of articles (6) appearing within the date range of 2000-2003. The former is suggestive of the enduring nature of previously developed conceptual constructs with the latter perhaps evidencing a shift in focus within the field from an organisational and strategic management based approach to a more diverse and discipline spanning interest. As there is a lack of citations of more recent articles (the most recent of which in 2006) this could signal a general restraint from the research community to accept newly published articles, however and more plausibly, it is the product of delayed temporal diffusion of research contributions as we would expect increased acceptance over longer time durations. Each over-arching theme will now be briefly discussed in relation to its contribution. Table 2 presents the four priority groups based on the information provided by the most influential articles.

Tabla 2. Key priority groups extracted from citation analysis

| Priority Grouping | # Papers | Field | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.- Sociological | 2 | Conceptually based. | Social elements mainly emphasising the impact of relations and the consequential influence that these can exert over different economic activities and behaviour |

| 2.- Cognition | 9 | Psychological or cognitive interests. | Entrepreneurial action, linking system-level theories to those of the individual. Notion of opportunity and decisionmaking. Individual-opportunity nexus. Decision models. Entrepreneurial intentions: behavioural model, predictions, cognitive biases. Idiosyncrasies involved in the decisionmaking processes. |

| 3.- Process | 6 | Allocating specific interest towards the core process of NVC. | Descriptive models of the creation process. Transitional phases in NVC. Perspective framework: individual, context and encompassing process. Required actions that lead to business creation. Relevance of business planning. Start-up activities. Properties of NVC. |

| 4.- Resources | 3 | Capital: Accumulated skills, experience, knowledge and finance. | Human (formal education, experience and business classes) and social (strong and weak ties) capital to achieve desired goals. Impact of social capital. Prior knowledge. |

Figure 2. Paper distribution based on year of publication and priority grouping |

|

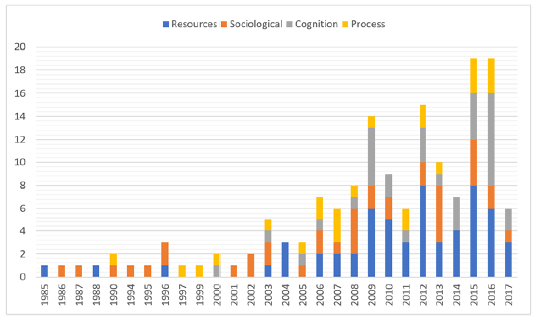

THEMATIC CLASSIFICATIONS

The main topical themes (Figure 3) from within articles were developed through manual extraction based upon in-depth analysis and identification of their purpose in relation to previously determined priority constructs. This relied on our own expert judgements - a process that is not uncommon in related research (Wang & Chugh, 2014). Themes were further constructed through the generation of secondary, tertiary and in some scenarios quaternary sub-groupings that were distilled through recurring themes presented in the papers and observed commonalities. These categories will now be discussed briefly in terms of their thematic contribution.

Figure 3. Paper distribution based on year of publication and priority grouping |

|

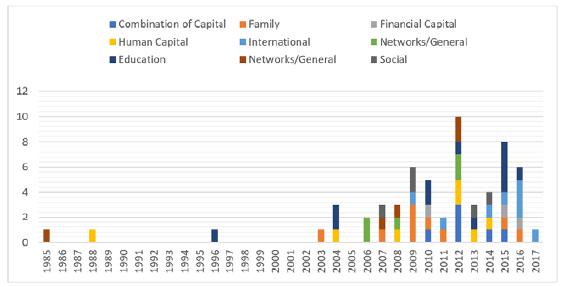

RESOURCES PRIORITY GROUPING FOCAL THEMATIC CONSTITUENTS

This classification captured articles concerned with advancing the issue of obtaining resources and the subsequent impact upon the creation, or discovery, of entrepreneurial opportunities and value. Papers with explicit emphasis towards resources, broadly defined as physical possessions, various forms of capital, and intellectual property, among other tangible and intangible value emitting assets, were conscious either as to how these commodities could be obtained or their influence toward NVC. This incorporated articles that considered the impact of the stockpile of personal knowledge, skills and abilities that through personal investment have been experientially built (human capital) (Mosey & Wright, 2007); that allow for the extraction of value from social infrastructure (social capital) (Davidsson & Honig, 2003) and finally, that permit access to, or attainment of, monetary funds (financial capital).

Thematic distribution analysis has indicated that social capital assumes the most influential role within the resource literature. Research attention is directed at a multitude of different themes (Figure 4). For instance, Lamine et al. (2014) focus on technology ventures highlighting the impact of social capital over entrepreneurial outcomes. Ferri et al. (2009) reflect upon the measurement of social capital, emphasizing its depth and richness whilst identifying that successful entrepreneurs are required to extract value from associative bonds with numerous stakeholders.

Figure 4. Thematic distribution of the Resources priority construct |

|

The underlying content and processes from such value extraction activities, themselves, emerge as a significant sub-category, entitled networking. This perspective is largely derivative of the belief that individuals are not in possession of all the necessary resources required to effectively transcend the NVC process. As consequence of such shortcomings it therefore becomes imperative that entrepreneurs are able to delve into socially constructed relationships to extract those aspects of which they are bereft. There is an explicit focus on the value that can be generated from social ties and relationships that often serve on an interchangeable basis. For example, Birley (1985) in her early contribution, based on the analysis of survey data, investigated the usage of both formal and informal networks in attempts to amass resources. It was determined that informal contacts tended to be the overriding source of choice.

From 2010 onwards, in recognising the interrelationships that underpin resource accumulation, there is a visible upward proliferation related to those articles concentrating on one or more forms of capital. Hmieleski et al. (2015), challenged the generally accepted acclaim that more capital permits greater benefits suggesting a more nuanced approach emphasising resource specificity for certain contexts. With the realisation that there are fundamental aspects that transverse, or certainly hold strong relationships, across all three types Schenkel et al. (2012) examined linkages between both human and social capital. This was not only carried out at a general level but so too within specific high and low technology environments. From the findings, it was claimed that certain systematic relationships exist irrespective of context.

Along a similar trajectory to those studies combining capital, although smaller in number, were financial capital papers which were associated mainly with the acquirement of pecuniary benefits from investment funds or startup financing. This has traditionally been viewed as a barrier towards venture formation and themes of study ranged from Frid et al. (2016) indication of financial health status being a key determinant of access to external investment, to topics of individual commitment (Frid et al., 2015) and, how and why finance is made accessible (Lam, 2010).

One highly mobile area in recent years is that of education. This is largely due to the perceived significant effect that it imposes towards the development of individuals equipped with the necessary attributes, mindset, and desire to successfully engage in entrepreneurially based activities (Kirby, 2004). For example, Lackéus & Middleton (2015) investigated how venture creation centred programmes can abridge entrepreneurship education and technology transfer, whilst Kickul et al. (2010) encourage the development of a cognitive infrastructure that allows students to seek more value-creating opportunities. A real resonating feature from educationally grounded papers is a clear emphasis toward experiential and action-based pedagogy to align more closely with “real” world challenges (Jones & Iredale, 2010; Rae, 2012).

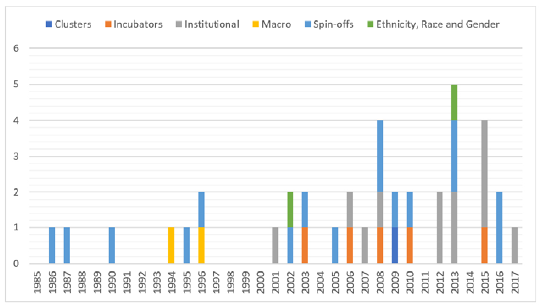

SOCIOLOGICAL PRIORITY GROUPING FOCAL THEMATIC CONSTITUENTS

The sociological category papers mainly deal with the beliefs and customary values that exist within a certain society and within a given temporal context. They are composed of two overriding secondary categories, namely those that focus on ethnicity, race and gender, and those that place environmental conditions at their core. Ethnicity, Race and Gender has received the least research attention (Figure 5) with only two studies tackling the issue. Thematic topics are implicated, firstly, with how ethnicity may have the potential to impact upon NVC. Lalonde (2013) discovered that the Arab culture exerts a significant influence through underlying beliefs and practices; such as those associated with its Bedouin heritage. And secondly, concerning gender equity supply and attainment by female entrepreneurs (Brush et al., 2002). This particularly interesting line informs us about the dearth of funding opportunities amongst the female demographic.

Figure 5. Thematic distribution of the Sociological priority construct |

|

As an enduring thread the environment has been identified both in terms of longevity and popularity in the sociological category. It was constructed by those publications that considered the specific contextual conditions through which ventures and their encompassing constituents have the potential to be nurtured. Upon deconstruction, a resultant five compositional contributors could be acknowledged, namely, institutional, clusters, spin-offs, incubators, and macro factors. Various studies (for example, Schwartz et al., 2013) investigated national institutional influence through the implementation of entrepreneurially conducive policies. Lounsbury & Glynn (2001) through an alternative cultural lens, considered how entrepreneurial stories can help generate legitimacy for new ventures concluding with the recommendation that reflection is needed upon societal and institutional norms when constructing such narratives. An interesting addition to this group was the article composed by Gavor & Stinchfield (2013) whom proposed that corruption can rather controversially contribute to increased NVC albeit to those ventures predominantly classified as necessity driven.

The emergence of clusters (or networks of independent businesses operating in collaboration with their geographically located counterparts to create added value) as a focus transpired via the workings of Engel & del- Palacio (2009) through their indication that the mobility of resources and knowledge derivatives from clusters act as a key source of entrepreneurial innovation. These clusters have often been created and enhanced through the incubation of new ventures which are analysed through best practice, characteristics, type, and their influence towards the successful transcendence of goal impediments (Atherton & Hannon, 2006; Schiopu et al., 2015). Other topical interests have included how incubators are governed and can be supported (Gstraunthaler, 2010).

A large portion (16 papers) of environmental research involved the study of spin-offs, or in other words, the benefiting from the extraction of opportunities and resources from previous experiences be it in university or within the work environment. These remain adherent towards the postulation that NVC is not a uniform process and is embedded through dependency on both situation and context. Content was centered around formation of either corporate, publicly funded, or academic spin-offs. Academic spin-off topics included social capital (Borges & Fillion, 2013); causality and effectuation (Schleinkofer & Schmude, 2013); relational credibility (Bower, 2003) and growth (Doutriaux, 1987). Whereas, public funded spin-offs were analysed predominantly in light of the technology transfer process (Upstill & Symington, 2002), and corporate ventures via the influence of adverse conditions and inspiration (Curran et al., 2016; Thorén & Brown, 2010).

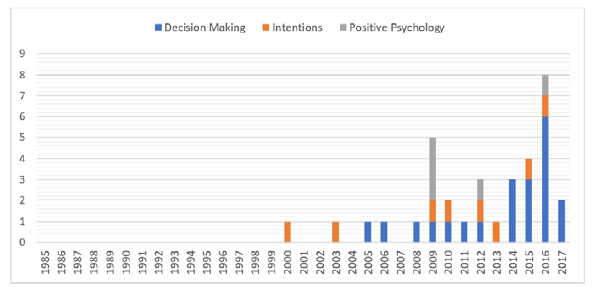

COGNITION PRIORITY GROUPING FOCAL THEMATIC CONSTITUENTS

Cognitive grouping publications are relatively nascent to the field (Figure 6) and are anchored via the thematic consideration of information processing by means of engaging mental frameworks for the purposes of evaluative decisions. These are based upon numerous input stimuli including the perception of opportunities and new business formation (Mitchell et al, 2002). Following on from this, the knowledge structures that provide the capacity to enact informed judgements within entrepreneurial NVC emerged as a strong and constant research area. Studies in this regard have ranged from the uncovering of central antecedents of the NVC decision making process (Zivdar & Imanipour, 2017) to longitudinally tracking the evolution of these cognitive processes over a prolonged duration of time (Reymen et al., 2015; Uygur & Kim, 2016).

Figure 6. Thematic distribution of the Cognition priority construct |

|

With this sustained monitoring emerges the assertion that as venture specific experience increases so too does the capacity for selective judgements. However, a hybrid form of decision-making or more specifically a combination of both effectual and causative logic appears to be best suited for success (Agogué et al., 2015). Effectual processes acting on a serendipitous trajectory are considered to complement entrepreneurial competencies including those associated with experimentation (Chandler et al., 2011) and risk-taking (Lehman et al., 2014). This highlights an influential standing for both personality and motivation when considering which judgements to make. These simplified decisive actions or heuristic endeavors are largely becoming of two heavily studied research perspectives. One in which evaluative inferences can be objectively made based upon individual preference and attractiveness, and another, that portrays an equivocal environment that necessitates enactment by the individual. These perspectives were focus of a number of articles, all adopting a process view combining both discovery and creation outlooks (Edelman & Yli-Renko, 2010; Stritar et al., 2016). The underlying belief resonates that perceptions and interpretative mechanisms of the individual coinciding with knowledge are decisive factors in NVC. Another article, however chooses to analyse at the firm-level highlighting the benefits that organisational learning can contribute to both discovery and formation activities (Lumpkin & Lichtenstein, 2005).

A second prominent and equally stable research area embraces the theoretical and empirically grounded notion that opportunities, be them discovered, created, or a composite of both, are preceded in the NVC process by the desire to engage in entrepreneurially based behaviours. Intentional themes under investigation align closely to four of the six lines of specialisation previously presented by Liñan & Fayolle (2015). For instance core intentionality models were compared by the hitherto mentioned highly influential priority contribution of Krueger et al. (2000). Personal-level (Pihie & Bagherie, 2013), gender-related (Manolova et al., 2012), and contextual (Schwarz et al., 2009) factors were all also studied.

The final emergent category of investigation was enacted from a positive psychology lens and is one that appears to be arriving to fruition in extant publications. Various efforts embodied a desire to further knowledge surrounding affectual or emotional components of NVC. Zampetakis et al. (2016) examined anticipated emotions of greek university “early stage career starters” (p. 33) concluding that a concoction of feelings is portrayed with those benefiting from vicarious others being more likely to conceive the process in a positive light. Hmieleski & Baron (2009) approach NVC from the scholarly assertion that entrepreneurs are accompanied by a dispositional positive outlook towards future occurrences even when this optimism may not be totally warranted. As such, they discovered that this over-confident and intuitive perception shares a negative relationship with subsequent performance of new ventures.

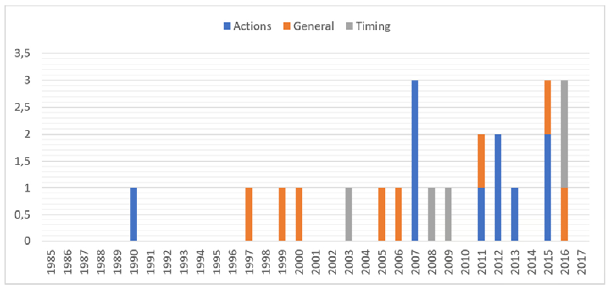

PROCESS PRIORITY GROUPING FOCAL THEMATIC CONSTITUENTS

Criteria for inclusion under the focal theme of process required a holistic approach, be it through relation with initial linear venture stage models or those that are more contemporary and interactive. This meant that the article took into explicit consideration either the associated transitional phases, actions and behaviours, or a combination of all three. Process is envisaged at a broader level in quest to explicate new venture formation. Studies embraced various common focal topics that could be demarcated into a trifactor of general process research, timing and actions.

General contributors sought to provide insights into the overall process and occupy a habitually consistent temporal interest (Figure 7). Themes range from Lichtenstein´s (2016) proposal of a symbiosis between entrepreneurship and underling systematic dynamics of complexity science to the phase specific examination of competency acquisition (Omrane & Fayolle, 2011). Additionally, Van Gelderen et al. (2006) upon guidance from Gartner´s (1985) template identified various factors that can be attributed to the success or indeed failure to create a business, and as consequence proposed a selection effect.

Figure 7. Thematic distribution of the Process priority construct |

|

Gartner et al. (1999), through study of a firm’s continuance ascertained that survival was underpinned by an amalgam of variants including entrepreneurial learning and a produced to order focus. In this paper, an academically developed venture screening process was pitted against experts in terms of predictive power with emphasis on entrepreneurial behaviour. From this, similarities are drawn directly to the study of Van Gelderen et al. (2006) as once again Gartner´s (1985) model was deployed as reference.

Critical incidents during formation and their timing were also contemplated in relation to NVC (perhaps an area that merits greater attention). Through highlighting shortcomings of previously established models, Kaulio (2003) discovered a total of 65 critical incidents across eight companies within an 18-month time-frame with finance and recruitment most frequented. Stayton & Mangematin (2016) sought to alleviate self-contrived limitations of previous venture creation models with special reference to those displaying an overemphasis towards activities through including a temporal dimension. Their concerted efforts result in the postulation that two overriding processes, product and organisational emergence, have to be managed under consideration of time as a key variant.

Alongside timing, Brush et al. (2008) via Katz & Gartner´s (1988) model tested the four cited properties of emerging organisations alerting us to the necessity of intentions, boundaries, resources and exchange. Findings that have been replicated since in subsequent research (Manolova et al., 2012). Advancements to Katz & Gartner´s model (1988) are claimed through the creation of linkages between these dimensions and intangible outcomes. Interestingly, a slower pace of progression was found to increase the likelihood of persevering in organising activities.

An influential area of study was related to actions required, or perceived to be necessary, in order to effectively engage in the NVC process. One form of business activity that emerged as a popular theme was the business model. Generally speaking, the collection of publications in this genre associated themselves with planning for the successful operating of an enterprise. A select number dealt with technology-based firms or the role of the internet in business formation. Muzellec et al. (2015), for example, presented an internet model derivative from a lifecycle interpretation representative of the dynamic and complex entrepreneurial ecosystem in which the internet creates. Further to this Gunzel & Wilker (2012) informed us to the influence that technology can exert on startup activities with the business model perceived as a facilitator of change. Additional topics included the creation of social ventures and the need to develop distinct models for this particular entrepreneurial form. There is an advocation for a strategical process hybrid model embedded in innovation and shared value (Florin & Schmidt, 2011).

DISCUSSION

This paper sought to advance the clarity of NVC via means of a systematic review of the surrounding literature guided by a citation analysis framework. To be more specific, an attempt was made at identifying the research themes receiving the most scholarly attention focusing mainly towards the topical content of relevant publications. This fine-grained approach differs and complements past research efforts in the area (Davidsson & Gordon, 2012). A key utility of the contribution is the influence exerted upon cumulative research efforts via rigorous and reliable methodology. The task was by no means a trivial undertaking due to the myriad of variants within the evolving process, however, the challenge posed of providing an harmonious (although not exhaustive) depiction of the landscape was embraced nonetheless.

A further four key contributions ensue. Firstly, a greater understanding of the NVC research arena is generated through identification of key research interests, both past and extant, that span across many differing disciplines. Key publications are signalled, and their interrelationships are considered. Secondly, indication is provided as to the origins and catalysts, in terms of intellectual foundations and theoretical underpinnings, of contributions through locating the seminal articles influencing the field´s evolution.

Thirdly, classification has afforded an up-to-date overview allowing for a more precise and explicitly interconnected approach to future research. Finally, it is proposed that this initial question centred on NVC research can assume the position as a forerunner to the formulation of further enquires through iterative processes. Thus the opportunity is afforded to build upon prior knowledge in pursuit of more nuanced interests.

It has become apparent that the research associated with venture formation adheres to its foregone characterisation in that it is composed of a multitude of influencing variables. Although this multidisciplinary composition creates a potential problem in ascribing a coherent and consistent framework from which to work, it does ensure a richness potential for the development of new avenues and enquiries that can continuously be derived and addressed.

That being said, it is vital that a concerted effort is made to prevent future efforts from bifurcation and drifting too far away from the focal concept. Ensuring relevance is maintained by constructively adding to its usefulness as opposed to its disparity is of paramount importance. Benefits derivative from diversity are commonly located in competitive contributions and synthesising activities as opposed to an increase in disaffiliation (Rousseau et al., 2008). Therein, lays a critical input of the present paper in that a common ground through four main priority themes within the scholarship have been exhumed and made explicit to the research community. Namely, research inspired by resources, sociological, cognitive, or process undertones.

It is clear that attention designated to each has not been equally distributed, however, it is through the collective recognition of these themes that numerous voids within the patchwork of NVC can be identified and suffused. Thus, future industry may benefit from a connectedness originating from the contextualisation of their contributions in reference towards these groupings. What has transpired, and indeed upholds the commonly held view, is that NVC is goal-directed and initiated through conscious deliberation (in most cases) by an individual. They will progress and regress through various phases seeking to sharpen boundary conditions and maximise transactional exchanges. In so doing new activities will be encountered, whilst there will also be a need to frequently repeat and recall upon previous behaviours.

In this way NVC involves numerous iterative actions that are performed at various temporal and spatial locations. By its nature it is a process of unfolding and emergence. Therefore, its examination needs to be taken as a continuous multi-event phenomenon in which situated key variables will hold impact, albeit to varying degrees, throughout the complete journey. Given its complex constitution much greater complexity in our thinking is required. This posture is reflective of continual change and becoming emphasising activities in continual flux in situ of products.

Substance metaphysics, although in recognition of process, dictates that substances are contingently acted upon by processes. For example, an entrepreneur along their venture creation journey is perceived as unchanging from one moment in time to the next. Instead, their actions and behaviours are incidental, however not essential, to be classified as an entrepreneur. This line of thought can easily be applied to the new venture itself, do we simply perceive change as happening to the new venture as it moves from one phase to the next? It may become a registered business or may have received investment funding, however these incidental “forces” are not essential for it´s classification.

Process thinking on the other hand, would determine a new venture as the constitution of a number of interacting processes amongst the four identified priority groupings. Attention would be shifted from the new venture itself, defined by a number of pre-requisite attributes, towards the ongoing inter-dependent assemblage of internal and external forces. An ontology founded upon such relations speaks of events that are experientially embedded and emerge out of these experiences (Hernes, 2010). The temporality of historical contingencies allows new events to develop making it imperative that they are considered. Individual actions and the interactions observed are precarious, they are not standalone entities however contingent upon relationships. What results is the realisation that the shaping of the process occurs over time through mutual experiences and is maintained through the associative powers of its actors. The NVC process becomes a harbourer of contingencies introducing the possibility for us to be creative and novel (Hernes, 2010). Contingencies are not pre-determined however latent and do not come with any apriori certainty. Moments transpire and attract flows that add to the observed forms, whilst also serving to generate different forms.

The pathway becomes intimately more idiosyncratic and a lot more sensitive to contextual variances. Indeed, it is purported to be inextricably linked to its contextual setting and any efforts towards extraction would therefore be to the detriment of our comprehension. However, research focusing on sociological issues, certainly in the current review, is arguably too self-indulgent and it may prove a worthwhile endeavor to span thematic boundaries in search of connections with other concepts. For example, we can consider the role of cognitions determining whether they are best taken as either constituents or dependencies of our surroundings.

Research focusing on cognitions has seen a boom in publications as of the year 2000 perhaps in response to Shane and Venkataraman´s (2000) introduction of the individual opportunity nexus that put greater emphasis on decision making processes. It appears to be progressing towards the acceptance of more dynamic outlooks which is promising. However, there remains large amounts of potential future contributions along this evolutionary temporal focus, especially, given its heavy reliance on the more orthodoxical variance-based theorizing.

Compression of variables, as variance theorizing does, perhaps is not best suited for a processual ontology (although it can be incorporated) given it´s focus on efficient antecedent variables and their ability to produce a clear outcome. Additionally, in contrast to process thinking, the temporal sequencing of these antecedents are taken as inconsequential. Time is an inescapable reality of NVC and it becomes impossible to separate experience without consideration of conscious reflection (Galloway et al., 2019).

This corresponds to a necessity to develop our understanding of the ever-changing and specific nature of NVC in which a multiplicity of decision-making scenarios are presented and a straightforward prescription is not plausible due to feedback loops and unpredictability.

Choices will be made and decisions taken through working hypotheses focused on the possibilities of what could potentially transpire. This draws us back to the inter-relatedness of contingencies as history helps to influence choices made. These of course could well lead to different events, not just as consequence of the varability associated with external conditions, but also through the fact that alternative decisions could have been made resulting in different effects (Sarasvathy, 2001).

Thus, the subjective experiences encountered within the related and continuous sub-processes may provide an authentic means to allay knowledge gaps. For example, one such trajectory that could prove valuable is the examination of how state-like emotions and their impact throughout the entirety of the process develop (Lackeus & Middleton, 2015). Indeed, another useful direction to increase theoretical precision could be the investigation of the temporal stability of the highly studied concept of entrepreneurial intent that can help convey how we can direct and sustain attention towards numerous actions during the complete pathway (Donaldson, 2019).

In fact, progress may act recursively on our desires to continue as action has been previously stated to define our cognitions (Webb & Weick, 1979). For example, and in alignment with the utility of goal pursuit, if we are successful in accumulating required resources this could serve as reification of perceptions stimulating an intent to continue. The entrepreneur will interact in recursive fashion with events and experiences, they will control certain facets but it is quite possible that in other situations they will be “forced” into behaviours altering the course taken (Callon, 1984).

Historically resources, and the transactions made to acquire these, have held a strong determining influence over the process (Jarillo, 1989). The resource priority group was discovered to be the most heavily studied and enduring. It certainly seems that the influence of the resource based outlook of the firm has transcended to various foci, particularly, in search of better clarity towards how the process of NVC unfolds. In correlation with strategic management approaches, more static views of resource accumulation and utilisation have embodied early research. However, there appears to be a shifting of focus towards more dynamic and knowledge based preferences across differing levels. This shift, alongside the more extant infused capital approaches, is essential if we are to truly embrace the notion of a dynamic and non-linear journey, whereby there is capacity to improvise, responding pragmatically to everchanging demands. Interesting possibilities remain at both the team and aggregate level to further develop the impact of resources upon NVC. For example, one might consider how these resources, from a contingency perspective, evolve and their composition varies within teams or, if member attrition occurs, how and if, these resources are compensated for.

Perhaps, what resonates most from the present review, even with admonishment decades in advance (Gartner, 2001), is a frequent disconnect in the quadrality of resource, sociological, cognitive, and process factors. A large portion of content tends to focus mainly on only one or few category bound elements and thus neglects the true, and widely acknowledged, complexity of the journey. These factors do not just originate from processes however are instead continuously and inextricably embedded within them (Rescher, 1996). In the current article a broad array of contexts and variants have been described highlighting their distinct contribution to the discipline, but arguably there is an omission of discussion concerning their holistic influence.

With this, the overview presented here goes some way to accommodate dialogue in the aim of binding multiple thematical, theoretical, and intellectual perspectives from a process position. This allows for, what we believe, is required from future research in the form of a more integrative stance, an ontology of relations, where thematic units seek to attend to, or at the very least ascertain relationships between all four identified priority constructs in time. These can then be both causally and theoretically inferred, between specialised interests and the process as a whole.

Concluding

CONCLUSION

The current article held the objective of providing an up-to-date thematic overview via systematic means of the main research interests that are being studied in relation to NVC. In achieving this aim, a comprehensive systematic review of the research surrounding NVC has been presented. Four broad priority constructs are explicated that are recommended as a foundation for future work allowing for the formation of more integrative relationships amongst nuanced interests in a disparate field. It is acknowledged that these foci are not discrete identities, however are interconnected across conceptual boundaries, thus clarity in relation to operalisation and definition serves as a prerequisite to any future research agendas.

The implications of the information presented ensures that the entrepreneurship academic community (and perhaps further afield) are provided with a nonexhaustive indication of the interests that drive study seeking explication towards creating a new enterprise. This can inspire and engage various scholars to find an area of curiosity to help further develop and advance, with accessibility to such research perceived as the overriding purpose of systematic reviews (Briner & Denyer, 2012).

More importantly, it provides an extant and generic overview from which nascent scholars can depart. Avenues are opened at, and across, various levels. In particular, an area that merits further elaboration is pacing of activities and progress achieved throughout the complete process, especially with time being perceived as a critical enabler of firm creation (Stayton & Mangematin, 2016). Additionally, cognition research should not feel emboldened to pursue such a restrictive agenda. Instead it can begin to consider the influence of interactive processes and how these impact upon our thoughts and consequent NVC efforts. Insufficient focus has been designated to cognitive and processual constructs in this regard.

Naturally potential entrepreneurs, educational practitioners, and policy makers, can benefit from the provision of information regarding the skills, knowledge, and variants perceived to have the greatest impact on business formation that also allow for reflective and evaluative processes. A process outlook affords a much more useful application given it´s orientation towards the more actionable “how”. Current research efforts signal the importance of the educational constructs of curriculum, technology, and pedagogy. Therefore, educational curricula and governmental policymakers should give serious consideration to all three in developing associated statute to ensure more substantial coverage of all contributing variants. Furthermore, an interesting direction may well be to analyse interactions between education and the creation of socially contributing enterprises (Noyes & Linder, 2015), a hitherto underappreciated topic of examination.

LIMITATIONS

The current systematic review was accompanied by a number of associated limitations which are important to acknowledge, however every possible effort was made to regulate their influence.

Firstly, the classification process of the accumulated dataset into the corresponding priority grouping represented a problematic and thought-provoking task due to the obscurity concerning the intersections between thematic units. This therefore required an informed judgement by the authors into what we subjectively believed to be the superceding focus of the article. In this regard a degree of care is advised. Withstanding this we are confident that each paper is representative of its subsequent classification.

Secondly, restriction methods implemented, above all, relating to the use of only one database and the exclusion of various sources and types of publication may have resulted in the omission of certain pieces of information and an uncomplete reflection of the field that impacts upon consequent generalisbility.

Thirdly, as aforementioned the temporal frame for the investigation only reached until 2017 so future research is encouraged to discover if the over-riding themes and groupings hold in contemporary studies. Finally, the purpose of the review was thematically, and therefore content based, with the overriding ambition to present a coherent depiction of the research associated with NVC. As such, no attempt was made towards a comprehensive analysis of the empirical findings within the publications therefore there is the possibility of a negation of key issues in academic research, for example, methodological factors.

Notes

NOTAS

1. For a similar and complementary study that has recently been published see Davidsson and Gruenhagen (2020) “Fulfilling the Process Promise: A Review and Agenda for New Venture Creation Process Research”.

2. The current review covers up to (and including) September 2017. Therefore, although a number of years have elaspsed it still provides a beneficial and comtemporary oversight of the field.

References

References

Agogué, M., Lundqvist, M., & Middleton, K. W. (2015). Mindful deviation through combining causation and effectuation: A design theory–based study of technology entrepreneurship. Creativity and Innovation Management, 24(4), 629-644.

Ardichvili, A., Cardozo, R., & Ray, S. (2003). A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 105-123.

Armitage, A., & Keeble-Allen, D. (2008, June). Undertaking a structured literature review or structuring a literature review: tales from the field. In Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies: ECRM2008, Regent's College, London (p. 35).

Atherton, A., & Hannon, P. D. (2006). Localised strategies for supporting incubation. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development.

Audretsch, D. B., Carree, M. A., & Thurik, A. R. (2001). Does entrepreneurship reduce unemployment? (No. 01-074/3). Tinbergen Institute discussion paper.

Baron, R. A. (1998). Cognitive mechanisms in entrepreneurship: Why and when enterpreneurs think differently than other people. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 275-294.

Bhave, M. P. (1994). A process model of entrepreneurial venture creation. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(3), 223-242.

Bird, B. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442-453.

Birley, S. (1985). The role of networks in the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 1(1), 107-117.

Borges, C., & Jacques Filion, L. (2013). Spin-off process and the development of academic entrepreneur’s social capital. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 8(1), 21-34.

Bower, D. J. (2003). Business model fashion and the academic spinout firm. R&D Management, 33(2), 97-106.

Briner, R. B., & Denyer, D. (2012). Systematic review and evidence synthesis as a practice and scholarship tool. Handbook of evidence-based management: Companies, classrooms and research, 112-129.

Brush, C. G., Carter, N. M., Greene, P. G., Hart, M. M., & Gatewood, E. (2002). The role of social capital and gender in linking financial suppliers and entrepreneurial firms: A framework for future research. Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 4(4), 305-323.

Brush, C. G., Manolova, T. S., & Edelman, L. F. (2008). Properties of emerging organizations: An empirical test. Journal of Business Venturing, 23(5), 547-566.

Busenitz, L. W., & Barney, J. B. (1997). Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations: Biases and heuristics in strategic decision-making. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(1), 9-30.

Callon, M. (1984). Some elements of a sociology of translation: domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of St Brieuc Bay. The Sociological Review, 32(1), 196-233.

Carree, M. A., & Thurik, A. R. (2005). Understanding the role of entrepreneurship for economic growth (No. 1005). Papers on Entrepreneurship, Growth and Public Policy.

Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B., & Reynolds, P. D. (1996). Exploring start-up event sequences. Journal of Business Venturing, 11(3), 151-166.

Chandler, G. N., DeTienne, D. R., McKelvie, A., & Mumford, T. V. (2011). Causation and effectuation processes: A validation study. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(3), 375-390.

Curran, D., O’Gorman, C., & Van Egeraat, C. (2016). “Opportunistic” spin-offs in the aftermath of an adverse corporate event. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development.

Davidsson, P. (2016). The field of entrepreneurship research: Some significant developments. In Contemporary entrepreneurship (pp. 17-28). Springer, Cham.

Davidsson, P., & Gordon, S. R. (2012). Panel studies of new venture creation: a methods-focused review and suggestions for future research. Small Business Economics, 39(4), 853-876.

Davidsson, P., & Gruenhagen, J.H. (2020). Fulfilling the Process Promise: A Review and Agenda for New Venture Creation Process Research. Entrepreneurship, Thoery and Practice, DOI: 10. 1177/ 1042 258720930991

Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301-331.

Denyer, D., & Neely, A. (2004). Introduction to special issue: innovation and productivity performance in the UK. International Journal of Management Reviews, 5(3–4), 131-135.

Denyer, D., & Tranfield, D. (2009). Producing a systematic review. In D. A. Buchanan & A. Bryman (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational research methods (p. 671–689). Sage Publications Ltd.

Delmar, F., & Shane, S. (2003). Does business planning facilitate the development of new ventures? Strategic Management Journal, 24(12), 1165-1185.

Donaldson, C., 2019. Intentions resurrected: a systematic review of entrepreneurial intention research from 2014 to 2018 and future research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(3), pp.953-975.

Doutriaux, J. (1987). Growth pattern of academic entrepreneurial firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 2(4), 285-297.

Edelman, L., & Yli–Renko, H. (2010). The impact of environment and entrepreneurial perceptions on venture-creation efforts: Bridging the discovery and creation views of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(5), 833-856.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532-550.

Engel, J. S., & del-Palacio, I. (2009). Global networks of clusters of innovation: Accelerating the innovation process. Business Horizons, 52(5), 493-503.

Ferri, P. J., Deakins, D., & Whittam, G. (2009). The measurement of social capital in the entrepreneurial context. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy.

Fetscherin, M., & Heinrich, D. (2015). Consumer brand relationships research: A bibliometric citation metaanalysis. Journal of Business Research, 68(2), 380-390.

Fitzsimmons, J. R., & Douglas, E. J. (2005). Entrepreneurial Attitudes and Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Cross-Culturals Study of Potential Entrepreneurs in India, China, Thailand and Australia.

Florin, J., & Schmidt, E. (2011). Creating shared value in the hybrid venture arena: A business model innovation perspective. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 2(2), 165-197.

Frid, C. J., Wyman, D. M., & Gartner, W. B. (2015). The influence of financial'skin in the game'on new venture creation. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 21(2), 1.

Frid, C. J., Wyman, D. M., Gartner, W. B., & Hechavarria, D. H. (2016). Low-wealth entrepreneurs and access to external financing. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research.

Forbes, D. P. (1999). Cognitive approaches to new venture creation. International Journal of Management Reviews, 1(4), 415-439.

Galloway, L., Kapasi, I., & Wimalasena, L. (2019). A theory of venturing: A critical realist explanation of why my father is not like Richard Branson. International Small Business Journal,37(6), 626-641.

Garfield, E. (1979). Is citation analysis a legitimate evaluation tool? Scientometrics, 1(4), 359-375.

Gartner, W. B. (1985). A conceptual framework for describing the phenomenon of new venture creation. Academy of Management Review, 10(4), 696-706.

Gartner, W. B. (2001). Is there an elephant in entrepreneurship? Blind assumptions in theory development. Entrepreneurship Theory and practice, 25(4), 27-39.

Gartner, W., Starr, J., & Bhat, S. (1999). Predicting new venture survival: An analysis of “anatomy of a startup.” cases from Inc. Magazine. Journal of Business Venturing, 14(2), 215-232.

Gavor, M. P., & Stinchfield, B. T. (2013). Towards a theory of corruption, nepotism, and new venture creation in developing countries. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 18(1), 1-14.

Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties [J]. American journal of sociology, 78(6), l.

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481-510.

Gstraunthaler, T. (2010). The business of business incubators. Baltic Journal of Management.

Gundolf, K., & Filser, M. (2013). Management research and religion: A citation analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(1), 177-185.

Günzel, F., & Wilker, H. (2012). Beyond high tech: the pivotal role of technology in start-up business model design. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 9,15(1), 3-22.

Hernes, T. (2010). Actor-Network Theory, Callon's Scallops and Process-Based Organization Studies. In Process, sensemaking and organizing (pp. 161-184). Oxford University Press.

Hmieleski, K. M., & Baron, R. A. (2009). Entrepreneurs' optimism and new venture performance: A social cognitive perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 52(3), 473-488.

Hmieleski, K. M., Carr, J. C., & Baron, R. A. (2015). Integrating discovery and creation perspectives of entrepreneurial action: The relative roles of founding CEO human capital, social capital, and psychological capital in contexts of risk versus uncertainty. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 9(4), 289-312.

Jarillo, J. C. (1989). Entrepreneurship and growth: The strategic use of external resources. Journal of Business Venturing, 4(2), 133-147.

Jones, B., and Iredale, N. (2010). Enterprise education as pedagogy. Education + Training, 52(1), 7-19.

Katz, J., & Gartner, W. B. (1988). Properties of emerging organizations. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 429-441.

Kaulio, M. A. (2003). Initial conditions or process of development? Critical incidents in the early stages of new ventures. R&D Management, 33(2), 165-175.

Kazanjian, R. K. (1988). Relation of dominant problems to stages of growth in technology-based new ventures. Academy of Management Journal, 31(2), 257-279.

Kickul, J., Gundry, L.K., Barbosa, S.D., and Simms, S. (2010). One style does not fit all: The role of cognitive style in entrepreneurship education. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 9(1), 36-57.

Kirby, D. A. (2004). Entrepreneurship education: can business schools meet the challenge?. Education + training.

Kraus, S., Rigtering, J. C., Hughes, M., & Hosman, V. (2012). Entrepreneurial orientation and the business performance of SMEs: a quantitative study from the Netherlands. Review of Managerial Science, 6(2), 161-182.

Krueger Jr, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5-6), 411-432.

Lackéus, M., & Middleton, K. W. (2015). Venture creation programs: bridging entrepreneurship education and technology transfer. Education + training.

Lam, W. (2010). Funding gap, what funding gap? Financial bootstrapping. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research.

Lamine, W., Mian, S., & Fayolle, A. (2014). How do social skills enable nascent entrepreneurs to enact perseverance strategies in the face of challenges? A comparative case study of success and failure. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research.

LaLonde, S. (2013). Trauma and healing: Global mental health in JMG Le clézio's desert. Literature and Medicine, 31(2), 199-215.

Lehman, K., Fillis, I. R., & Miles, M. (2014). The art of entrepreneurial market creation. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 16(2), 163-182.

Lichtenstein, B. (2016). Emergence and emergents in entrepreneurship: Complexity science insights into new venture creation. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 6(1), 43-52.

Liñán, F., & Fayolle, A. (2015). A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(4), 907-933.

Lounsbury, M., & Glynn, M. A. (2001). Cultural entrepreneurship: Stories, legitimacy, and the acquisition of resources. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6–7), 545-564.

Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135-172.

Lumpkin, G. T., & Lichtenstein, B. B. (2005). The role of organizational learning in the opportunity–recognition process. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(4), 451-472.

Manolova, T. S., Brush, C. G., Edelman, L. F., & Shaver, K. G. (2012). One size does not fit all: Entrepreneurial expectancies and growth intentions of US women and men nascent entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 24(1-2), 7-27.

McMullen, J. S., & Shepherd, D. A. (2006). Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 132-152.

Mitchell, R. K., Busenitz, L., Lant, T., McDougall, P. P., Morse, E. A., & Smith, J. B. (2002). Toward a theory of entrepreneurial cognition: Rethinking the people side of entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(2), 93-104.

Moore, C. F. (1986). Understanding Entrepreneurial Behavior: A Definition and Model. Academy of Management Proceedings, 1, 66-70.

Mosey, S., & Wright, M. (2007). From human capital to social capital: A longitudinal study of technology– based academic entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(6), 909-935.

Muzellec, L., Ronteau, S., & Lambkin, M. (2015). Twosided Internet platforms: A business model lifecycle perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 45, 139-150.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242-266.

Noyes, E., & Linder, B. (2015). Developing undergraduate entrepreneurial capacity for social venture creation. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 18(2), 113-124.

Omrane, A., & Fayolle, A. (2011). Entrepreneurial competencies and entrepreneurial process: a dynamic approach. International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 6(2), 136-153.

Pihie, Z. A. L., & Bagheri, A. (2013). Self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention: The mediation effect of selfregulation. Vocations and Learning, 6(3), 385-401.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Bachrach, D. G., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2005). The influence of management journals in the 1980s and 1990s. Strategic Management Journal, 26(5), 473-488.

Rae, D. (2012). Action Learning in new creative ventures. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 18(5), 603-623.

Rescher, N. (1996). Priceless knowledge?: natural science in economic perspective. Rowman & Littlefield.

Reymen, I. M., Andries, P., Berends, H., Mauer, R., Stephan, U., & Van Burg, E. (2015). Understanding dynamics of strategic decision making in venture creation: a process study of effectuation and causation. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal,9(4), 351-379.

Reynolds, P. D. (2017). When is a firm born? Alternative criteria and consequences. Business Economics, 52(1), 41-56.

Rhaiem, K., & Amara, N. (2019). Learning from innovation failures: a systematic review of the literature and research agenda. Review of Managerial Science, 1-46.

Rousseau, D. M., Manning, J., & Denyer, D. (2008). 11 Evidence in management and organizational science: assembling the field’s full weight of scientific knowledge through syntheses. The Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 475-515.

Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 243-263.

Schenkel, M. T., D'SOUZA, R. R., & Matthews, C. H. (2012). Entrepreneurial capital: examining linkages in human and social capital of new ventures. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 17(02), 1250009.

Schiopu, A. F., Vasile, D. C., & Ţuclea, C. E. (2015). Principles and best practices in successful tourism business incubators. Amfiteatru Economic Journal, 17(38), 474-487.

Schleinkofer, M., & Schmude, J. (2013). Determining factors in founding university spin-offs. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 18(4), 400-427.

Schwartz, M., Goethner, M., Michelsen, C., & Waldmann, N. (2013). Start-up competitions as an instrument of entrepreneurship policy: The German experience. European Planning Studies, 21(10), 1578-1597.

Schwarz, E. J., Wdowiak, M. A., Almer–Jarz, D. A., & Breitenecker, R. J. (2009). The effects of attitudes and perceived environment conditions on students' entrepreneurial intent. Education+ Training.

Shane, S. (2000). Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Organization Science, 11(4), 448-469.

Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217-226.

Stayton, J., & Mangematin, V. (2016). Startup time, innovation and organizational emergence: A study of USA-based international technology ventures. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 14(3), 373-409.

Stritar, A., Brčić, A., Drnovšek, F., & Malvasio, V. (2016). Overview of ethno-folkloric burns in the Republic of Slovenia. Annals of Burns and Fire Disasters, 29(1), 9.

Thoren, K., & Brown, T. E. (2010). The Sarimner effect and three types of ever-abundant business opportunities. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 2(2), 114-128.

Upstill, G., & Symington, D. (2002). Technology transfer and the creation of companies: the CSIRO experience. R&D Management, 32(3), 233-239.

Uygur, U., & Kim, S. M. (2016). Evolution of entrepreneurial judgment with venture–specific experience. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 10(2), 169-193.

Van Gelderen, M., Thurik, R., & Bosma, N. (2006). Success and risk factors in the pre-startup phase. Small Business Economics, 26(4), 319-335.

Wang, C. L., & Chugh, H. (2014). Entrepreneurial learning: Past research and future challenges. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16(1), 24–61.

Webb, E., & Weick, K. E. (1979). Unobtrusive measures in organizational theory: A reminder. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(4), 650-659.

Webster, F. A. (1976). A model for new venture initiation: A discourse on rapacity and the independent entrepreneur. Academy of Management Review, 1(1), 26-37.

Wright, M., & Marlow, S. (2012). Entrepreneurial activity in the venture creation and development process. International Small Business Journal, 30(2), 107-114.

Zampetakis, L. A., Lerakis, M., Kafetsios, K., & Moustakis, V. (2016). Anticipated emotions towards new venture creation: A latent profile analysis of early stage career starters. The International Journal of Management Education, 14(1), 28-38.

Zivdar, M., & Imanipour, N. (2017). Antecedents of new venture creation decision in Iranian high-tech industries: Conceptualizing by a non-teleological approach. The Qualitative Report, 22(3), 732.