Article

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.18845/te.v15i1.5388

TRADE FINANCE CONSTRAINS AS A BARRIER FOR CHILEAN SERVICES INTERNATIONALIZATION

RESTRICCIONES DE FINANCIAMIENTO AL COMERCIO COMO BARRERA A LA INTERNACIONALIZACIÓN DE LOS SERVICIOS CHILENOS

TEC Empresarial, Vol. 15, n°. 1, (January - April, 2021), Pag. 2 - 19, ISSN: 1659-3359

AUTHORS

Dorotea López

Instituto de Estudios Internacionales,

Universidad de Chile, Santiago,

Chile

dolopez@uchile.cl.

![]()

Felipe Muñoz

FDDI Invited Researcher, Fudan

University e Instituto de Estudios

Internacionales, Universidad de

Chile, Santiago, Chile.

fmunozn@uchile.cl.

![]()

ABSTRACT

Abstract

The growing importance of trade in services in the international economy motivates the study of different factors that may influence the development of this sector. This paper seeks to contribute to the scarce research on access to financing for the internationalization of services. Through a survey, we analyze the perception of Chilean services exporters about access to financing instruments for trade, and whether this constitutes an obstacle in the process of internationalization or not. For companies that participated in the study, access to trade financing is not a barrier for exports. However, these results vary according to characteristics of the companies.

Keywords: Trade finance, services internationalization, Chile

Resumen

La creciente relevancia del comercio de servicios en la economía internacional motiva el estudio de los diferentes factores que pueden influir en el desarrollo del sector. Este artículo busca contribuir a la escasa literatura sobre el impacto de la falta de acceso al financiamiento para la internacionalización de los servicios. Por medio de una encuesta, analizamos la percepción de los exportadores de servicios chilenos sobre el acceso a instrumentos financieros para el comercio y si este acceso, o la falta de, constituye un obstáculo en su proceso de internacionalización. Entre las empresas que participaron en el estudio, el acceso al financiamiento para el comercio no es considerado una barrera para las exportaciones. Sin embargo, estos resultados varían según las características de las empresas.

Palabras clave: Financiamiento al comercio, internacionalización de servicios, Chile

Introduction

1. Introduction

For decades, international trade was concentrated in goods. Before the emergence of information and communication technologies (ICTs), the share of services in global trade was small (except for transport and tourism), as most were non-tradable. Since the 2000s, services are becoming increasingly important in world trade. Its dynamics are related to changes in production, the rise of new technologies, and the increase liberalization and removal of domestic barriers, all which have allowed that now-a-days services account for at least 20% of world trade (despite the remaining problems regarding their classification and measuring) (WTO, 2015). In addition, trade in services has shown much less volatility than trade in goods, particularly during periods of economic crisis (Borchert & Mattoo, 2010).

Services have their own characteristics, which play a fundamental role in the way companies engage in international markets. In the literature, various models and conceptual frameworks have been developed for services (Cicic et al., 1999) and specific sectors (McQuillan & Scott, 2015) in order to capture these unique characteristics, most from marketing perspective (Grönroos, 1999, 2016; Javalgi & Martin, 2007). Studies have review the impact of technology and other changes in the rapid internationalization of services firms (Miozzo & Soete, 2001).

Also, an important body of the literature has tried to identify those obstacles and barriers faced by services exporters, particularly SMEs (OECD, 2009). Traditional barriers usually refer to the lack of data and governmental policies to protect domestic providers, as this limits market admittance of foreign services providers (Borchert et al., 2013; Samiee, 1999). Most of the literature has focused on firms own characteristics and their impact in internationalization success (Bianchi, 2009; Brush et al., 2015; Gaur et al., 2014; Javalgi & Grossman, 2014; O'Farrell et al., 1996; Shaw & Darroch, 2004). Specific obstacles for services exporters may be identified on institutional frameworks, such as closed markets for third country provision (or with high limitations) or markets under monopolies or imperfect competition; domestic constrains such as lack of finance instruments, lack of governmental support, policies design for goods not tailored for services, and internal characteristics of the companies, including lack of expertise, impediments to their integration into business networks, and financial constrains amongst others.

One of the most common problems identified that services providers must face when becoming global is the access to financial resources, particularly for export and import operations (Schmidt-Eisenlohr, 2013). This problem is faced by both goods and services companies, particularly SMEs in developing countries, and becomes especially relevant for services businesses as they usually do not have physical assets as liability for traditional financial system operators. Therefore, many companies do not involve in international trade, or have to do it using their own resources, limiting their expansion possibilities. Various attempts have been made in order to expand the access to financial instruments for these companies, including Aid-for- Trade initiatives (Auboin, 2007; Malouche, 2009); but is still an important obstacle in internationalization processes.

Despite its growing importance, little research has been done on the impact of trade finance on services exports, as most literature has focused on merchandise flows. This paper intends to analyze access to trade finance for Chilean services exporters, and whether it is perceived as an obstacle in the process of internationalization of services or not. Through a survey we tried to assess companies’ perceptions, controlling for their subsectors, size, and export level, amongst other variables. The role of financial institutions and government agencies was included in the study.

After this introduction, the first section reviews the relevant literature exploring trade finance. The second section will present the methodological approach and descriptive statistics of our sample. The results of the survey and its analysis are presented at the third section. Finally, some conclusions and policy recommendations will be drawn in the last section.

TRADE FINANCE: LITERATURE REVIEW

International trade carries larger financial constrains than domestic trade, as noted by Auboin & Engemann (2013, p. 4): “… first, international transactions involve a higher level and number of risks, such as the exchange rate risk, the political and non-payment risks. Second, internationally active firms have larger financing needs, explained by the time lag between actual production of the good and its delivery”. Due to these characteristics, various financial instruments have developed over time to overcome the risks and delays faced by international transactions. We may summarize these instruments in payments (cash operations, letters of credit, document collections, and open accounts), insurance (export credit, foreign exchange, and other insurance schemes), and working capital (working capital, factoring and other loans directed to exports production).

During the literature review, it was evident that studies related to the export finance, in general, consider goods and services, but in fact, they do not emphasize services. For example, from the analysis of domestic financial constraints on the entry in heterogeneous companies trade, with different export volumes, it was found that liquidity constrains prevented them to engage in international trade; therefore, it was concluded that financial underdevelopment hinders exports (Chaney, 2016; Manova, 2013). Humphrey (2009) surveyed the impact of trade finance constrains in sub-Saharan African horticulture and garment companies, and found that exchange rate volatility and demand contractions are the most important effects over their companies´ revenues and financial stability. Antras & Foley (2015), using data from a company that exported frozen and refrigerated food products, found out that companies covering higher costs to obtain external capital were the ones who most needed financing for their transactions. Companies in weak institutional environments are able to overcome the limitations of such environments if they can establish a relationship with their business partners; in this way, trade represses the impact of macroeconomic and financial crises.

Empirically, some authors suggest that credit constrains have a negative impact over exporting companies performance (Greenaway et al., 2007; Muûls, 2015; Paravisini et al., 2014). Wagner (2014) presents a literature review on papers addressing how credit constraints affect exports, by using companies data. Even though he finds out that financial constraints are important for the organizational decisions on export, he raises some issues to be considered in future research: the use of indirect measures, the non-comparability of results due to differences in the empirical models, limitations due to severe measures of credit constraints for smaller firms, a relative small number of exporters, and short time spans that make it difficult to generalize conclusions.

The evidence points out that a company with low collateral to secure trade finance instruments (mainly export credits) tends to export less, which is the case of most services. Unfortunately, studies about access of services to export finance are scarce, and the few available studies do not take into account cases of developing economies. For example, the United States International Trade Commission (USITC) presented a study about the domestic and global operations of American SMEs. This report, made for the 2000´s, provided the perspective of US SMEs concerning impediments to exporting, including access to financing. It shows that more than 40% of SMEs exporting services considered obtaining financing as one of the main difficulties for exporting, compared to only 30% of manufacturing SMEs. Also, it is important to note that there is a significant difference in terms of access to financing between an SME and a large company. Although this is true for both goods and services, it becomes relevant for services industries, as their access capabilities to financing are reduced due to the lack of collaterals. The same study shows that 46% of SMEs in the service sector considered the process of obtaining financing for crossborder transactions to be onerous, compared to only 17% of the large companies in services.

The authors above made a general analysis about the impact of financial shocks on international trade. The effects in services trade is different. Borchert & Mattoo (2010) showed in a study for India that the shortage of financial instruments during the financial crisis of 2008 had lesser impact on services exports. Amongst the reasons to sustain this, they counted that many services were delivered through digital environments across borders (digital trade), which reduced their cost compared to domestically provided services; likewise, that advance payments and factoring contributed to meet financing needs, as companies did not have to purchase inputs or stocks for their provision, contrary to the production of goods, where financing for stages before commercialization became crucial,; moreover, services were found to be relative independent from debt finance. On the other hand, the same authors pointed out that this latter result may as well set the fact that financing working capital poses quite a challenge to the service companies, as nothing tangible may serve as collateral, a generic problem in services provision.

Services might be less sensitive to credit crunches (Ariu, 2016). Payments are faster for services: as production and consumption often coincide, payments are made in the same period as provision, while for goods, delivery times delay payments; therefore, for services the risks of shipping delays are very low. Moreover, this absence of payment delays lowers the need of export finance insurance. It is possible that service exporters do not request trade finance because their services are intangible and highly personalized; therefore, they have little value outside the seller-buyer relationship and can hardly be used as collateral. Definitely, the minor impact of the global financial crisis of 2008 on trade in services was the lesser dependence on financing instruments. Ahn et al. (2011) showed that “exporters whose financial institutions became unhealthy cut back on exports more than other firms, and imports declined more in sectors that had greater external financial dependence.”

As it has been evidenced in the previous studies, the limitations of service companies to access financing differ from those of manufacturing companies. In the other hand, their necessities are also different. A comparison of the proportion seeking additional finance, across various groups of enterprises in the Cambridge survey covering the years 1987–90, showed that there was little difference between manufacturing and services, whereas the Bolton survey found that manufacturing companies were far more likely (32% in the previous two years) to have sought additional finance than service firms (20% in previous two years) (Hughes, 1997).

In conclusion, there is abundant literature available about the impact of trade finance on exports, but there are still gaps to be filled. Most empirical analysis have focused on goods industries, while studies on services are scarce. Also studies with approaches in this area and related to SMEs in developing countries are uncommon. This document attempts to cover the lack of research on export financing and internationalization of services exporting companies.

Methods

METHODOLOGY

As stated before, most studies regarding access and effects of trade finance have focused on goods companies, leaving behind attention on services companies. In order to fill the gap in literature and understand trade finance instruments access of services firms, we conducted a survey among Chilean services companies. To reach a representative number of enterprises, companies included in the study came from specific services chambers (architecture, international technology and communication, engineer, amongst others) and ProChile1. The survey was composed of three parts: companies’ characterization, exports’ characterization, and access to trade finance instruments2. An online questionnaire was sent to services companies CEO CFOs, and international markets managers between October 2016 and May 2017. A total of 56 companies answered the complete survey. Table 1 presents the characterization of the Chilean service companies in the sample. The survey was complemented with in-depth semi-structured interviews with key actors within the industry, that allowed us to comprehend the actual impact of access to trade finance in services internationalization.

As shown in Table 1, the sectorial distribution of the sample reflects the heterogeneity of services activities. 19,6% of the companies in the sample belonged to the business services sector; 12,5% to communication sector; 7,1% to architecture, and each of the remaining sectors represented around 3,6% of the participation. To characterize the companies according to their size, they were consulted for their total annual turnover3, including both their sales in Chile and their exports. Most of the sample, 42,8%, was composed of small companies, while large companies represented only 21,4% of it.

Table 1. Sample characterization

| Sectorial distribution | |

|---|---|

| Business services | 19,6% (11) |

| Communication | 12,5% (6) |

| Architecture | 7,1% (4) |

| Construction & related | 3,6% (2) |

| Education | 3,6% (2) |

| Transport | 3,6% (2) |

| Accounting | 3,6% (2) |

| Others | 48,2% (27) |

| Annual firm´s turnover | |

| Micro | 19,6% (11) |

| Small | 42,8% (24) |

| Medium | 16,0% (9) |

| Large | 21,4% (12) |

| Total sample | 56 |

Regarding the number of employees, it was remarkable that 80% of the companies had less than 50 employees; that meant an average of 31 employees per company. Following gender gaps in Chile, the number of men employees (22) doubled the women’s ones (11), and only 30% of the companies had equal number or more women than men in their payroll.

CHILEAN SERVICES EXPORTS & TRADE FINANCE

In order to split the sample according to companies exporting experiences, the first question asked was if the company was involved in international trade transactions, particularly in exporting. As shown in Figure 1, 73,9% of the companies that participated in this study exported services.

Figure 1. Does your company export services? |

|

| Source: the authors |

Although our study concentrated in the access to finance instruments for exporting businesses; nonexporting companies where not eliminated from the sample, and interesting information arose from them. At the time of the research, non-exporting companies were mainly concentrated amongst small and micro enterprises. First, we identified a group of companies that had no interest in exporting, either because they were in the process of consolidating in the domestic market, or because of the nature of their business they were not allowed to do it (as in the case of companies that represented foreign firms in Chile).

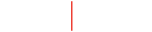

For companies that had achieved internationalization, the percentage of their exports was still very small compared to total revenues. Among those surveyed, 52,9% declared that exports represented less than 10% of their total turnover. 23,5% of the companies declared that exports represented up to 25%. Questioned about the amount of their production destined to exports, 11,8% of the companies said that between 26% and 50% of their sales were going abroad. Only 5.9% of the companies declared that their sales abroad represented up to 100% of their total sales (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Percentage of companies according to share of exports in total sales |

|

| Source: the authors |

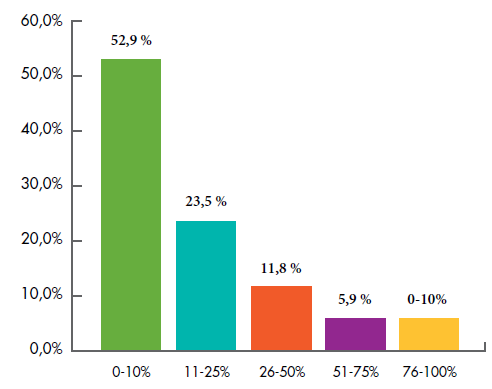

When analyzing the destination markets of their exports (Figure 3), we found a concentration of them in Latin America (67%) and smaller amounts in North America (17%), Asia (11%), and Europe (5%). It is interesting that when asked about which markets companies would like to enter in the near future, Latin American countries were again the main preference, followed by the United States and European economies.

Figure 3. Exports destination |

|

| Source: the authors |

In order to determine if access to financial instruments was perceived as a barrier for their international operations, companies where asked to identify the main barriers they faced in their export process. When reviewing the reasons that do not allowed this enterprises to trade internationally, those who would like to engage in international trade differed as shown in Figure 4: marketing (43,8%), market costs (37,5%), cultural and idiomatic differences (31,3%), and local networks (31,3%) were perceived as the most important problems companies faced when exporting their services. To a lesser extent, access to distribution networks (25%), logistics (18,8%), and financial access (12,5%) were mentioned. Companies did not have financial support to engage in international transactions; their own capital was insufficient, or they found that risk did not worth it. Other factors influencing negatively these companies´ internationalization included ignorance of the markets and, in particular, of their potential to enter those markets, to generate local networks, and to seek strategic partners and alliances.

Figure 4. Main perceived barriers to export* |

|

| Source: the authors *Note: It was possible to select more than one option in the survey |

The above results are very similar to the results reported by the World Bank in Enterprise surveys data for Chile (2010). This survey included the Chilean companies' perception of the constraints in relation to issues such as corruption, crime, finance, companies characteristics, gender, informality, infrastructure, innovation and technology, performance, regulation and taxes, trade, workforce. In the survey we conducted the constraints identified by Chilean services companies; it was found that 12,9% of them identified access to financing amongst the main ones (Figure 5). Although in that survey, the type of financing was not specified in the question, the result was consistent with the result obtained in our study.

When analyzing the perception of the companies on financial access as a barrier to their internationalization process, differences in the answers according to the size of each one of the companies arose.

Figure 5. Enterprise surveys data for Chile (2010), major constraints identified by services sector (% of companies identifying each factor as a major constraint) |

|

| Source: the authors, based on Enterprise surveys data for Chile (2010) |

For the above, we developed further investigation through different questions to deep in the financial trade constrains. In the interviews with key stakeholders, we were able to assess that difficulties in obtaining financing affected more intensely small companies, which was reinforced by an almost unanimous answer of the companies with turnover below 16 million dollars, when affirming that access to financial instruments was a potential barrier to their operations. On the other hand, only 33% of large companies believed that access to financing could limit their operations. Capital and financial access might not have been perceived amongst the main barriers, as shown in Table 2, because when analyzing the way firms financed their international trade operations, we found that most companies, around 75%, only engaged in foreign transactions when own funds allowed them to explore these opportunities . Financial instruments such as letters of credit accounted for less than 20% of them. For most services, companies access to financial instruments was not a possibility; only when own funds allowed them to secure international operations, they engaged in them. Therefore, bigger companies tended not to see finance as a barrier, as they provided their own financial schemes out of their own assets. As comparison, in countries such as Ireland, less than 50% of services’ companies use own resources for their internationalization processes, as they have access to traditional sources or government sponsored programs that ensure their entry into financial markets (InterTradeIreland, 2014).

Tabla 2. Payment conditions in export of services*

| Payment form | |

|---|---|

| Wire transfer | 75% |

| Credit card | 25% |

| Others | 6% |

| Payment terms | |

| Cash | 6% |

| 30 days | 44% |

| 60 days | 44% |

| 90 days | 6% |

| More than 90 days | 31% |

| Foreign payment currencies | |

| Dollar | 94% |

| Euro | 25% |

*Note: It was possible to select more than one option in the survey.

Source: the authors

Whereas the majority of the companies that participated in the study leveraged their activities with their own financing (Figure 6), we considered it necessary to find out more about commonly used financial instruments that would allow them to achieve sustainability for their businesses. In Table 2, data relate to foreign trade operations. When consulted on the payment form of their exports, more than 70% of the companies mentioned wire transfer and credit card. This is consistent with the previous findings regarding the way companies finance their international transactions, where financial institutions intermediation is secondary. As most export operations are being financed with own funds, payment terms and times become critical. The potential risk of insolvency or non-payment is bared by the export company, and the longer the payment is delayed, the lesser the working capital would be available. Most transactions are paid between 30 and 60 days later; although, for most companies cash or upfront funds would be the best deal, US dollar continues to be the currency used for international operations, while Euro represents a small share, mainly linked with operations made with economies in the Euro zone (especially Spain).

Figure 6. Financial instruments used for exporting operations* |

|

| *Note: It was possible to select more than one option in the survey.

Source: the authors, based on Enterprise surveys data for Chile (2010) |

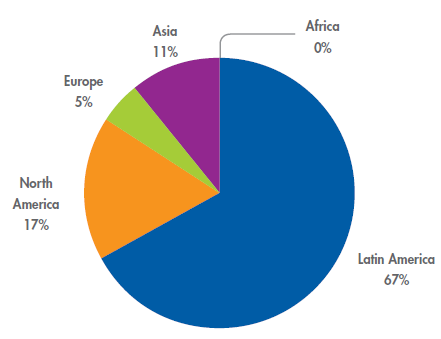

Another instrument we surveyed about were foreign exchange insurances. In a country with free floating exchange rates, appreciation or depreciation of the exchange rate may impact companies’ competitiveness and profits. Therefore, we could suspect that those enterprises engaged in international trade could secure their operations by incorporating this kind of insurance policies. In Ireland, insurance penetration is very low, in around 18% of the transactions, which may be explained for the extent of operations being made in Euros; but in India, which may be more similar to the Chilean case, a highly developed credit insurance market mainly focused on exporting services, with products worked out to deal with the particularities of the sector, has arisen (InterTradeIreland, 2014). Nevertheless, most of the companies surveyed (75%) do not operate with foreign exchange insurances (Figure 7). Amongst the reasons behind this large underutilization of these instruments, ignorance of their existence or scope may explain this phenomenon, as it is viewed below.

Figure 7. Do you use foreign exchange insurances? |

|

| Source: the authors |

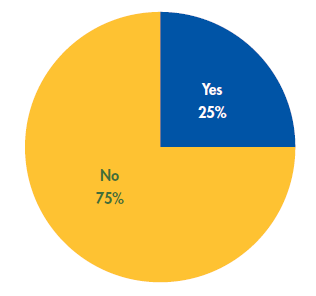

The lack of knowledge about the financial instruments that can be used in international transactions was also evident when credit insurance was consulted. Over 90% of the total sample did not know about this type of protection and from those who did, no one used it in the export process (Figure 8). In addition to ignorance, problems were identified in the contracts as a result of the complexities implied in them or the still very high costs for the amounts of transactions that were handled.

Figure 8. Do you know about credit insurances for services exports? |

|

| Source: the authors |

The development of credit insurance along with the advantages of the protection granted can be considered as guarantees for obtaining credits and, in some cases, serve as an incentive for companies to explore riskier markets. There are companies that, due to the nature of their services, have secure payment guarantees, such as temporary licenses or communication flows. On the other hand, ignorance of insurance may have as a consequence what could be already observed since we did our inquiries: that the companies that export services have concentrated their sales on few clients, whose reliability in payment is very high, such as large multinational companies or Chilean retail, among others; or they have sought security by working with foreign parent companies.

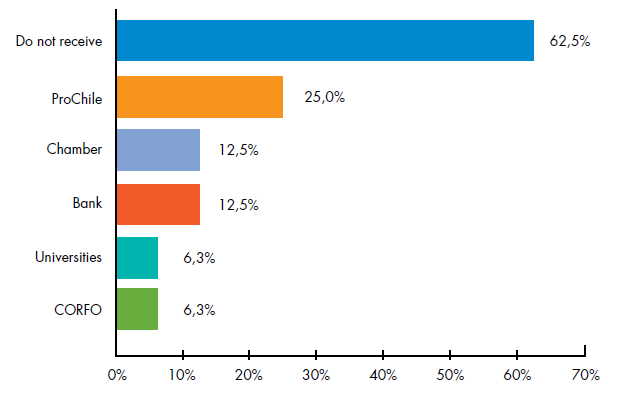

Finally, we asked companies about the support they had received in order to engage in international trade transactions. As shown in Figure 9, more than 60% declared not to have received any kind of support. ProChile, the public agency for export promotion, was the most often mentioned entity in the survey, with 25% of the sample that recognized their work. Taking into account that ProChile has stated as a priority the work with SMEs and services exporters, this percentage is low. Banks, Commerce Chambers, CORFO (Chilean governmental economic promotion agency), and universities ranked far behind. These results are explained by a characteristic of Chilean enterprises, which tend to work alone, without government’s or other organization’s support. Lack of associationism has been identified by various studies as one of the most important failures in the internationalization process of Chilean companies.

Figure 9. Which institution supports you when exporting?* |

|

| *Note: It was possible to select more than one option in the survey.

Source: the authors |

In this context, they were also asked about one specific program regarding trade finance, COBEX by CORFO (Figure 10). Over 90% of the sample did not know about this program, which helps firms engaging in international trade transactions to access the financial system when they do not have enough collateral. This may in part explain the low share of companies that subscribe to credit insurance, as most of them do not know about the existence of this kind of schemes. The high level of ignorance of these programs refers, firstly, to a problem in particular, inefficiency in the availability of information to stakeholders. This is reaffirmed by different stakeholders from both public and private sectors, who acknowledge that most financial instruments implemented by the government have been designed for traditional sectors (manufactures and agricultural commodities), and that there is a lack of expertise regarding the specific structure and needs of the services sector. Secondly, ignorance points to scarce publicity, as CORFO´s instruments are mainly given through commercial banks intermediation; therefore, most exporters do not know of their existence (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Do you know about CORFO´s guarantees for trade, COBEX? |

|

| Source: the authors |

In general, we can appreciate that the problem of access to sources of financing for the development of the export process of services companies, even though not being the principal barrier identified, is relevant one for their internationalization process. Also, we can conclude that this problem concerns all companies, regardless of size or category; besides, that businessmen ignore much about possible sources of financing, internal and external, and above all, about other financial instruments such as credit insurance.

In general, this research shows that access to financial instruments for trade does not represent the primary barrier for the internationalization of Chilean service companies. This barrier may be explained by the lack of awareness, among the companies, of the advantages that they represent for the financing of their operations. Few companies using financial supports for their business development, most of the respondents confirmed that they had encountered difficulties when accessing financial instruments to increase their production, develop new projects, or maintain the sustainability of their businesses. For this reason, Chilean service companies have made it a common practice to use their own funds to internationalize. In this sense, it was also identified that many companies assume that there are no adequate instruments to finance their international activities. Therefore, despite the existence of some financial instruments that can benefit Chilean companies that export services, there is total ignorance about them.

Concluding

FINAL REMARKS

Due to its characteristics, exporting services is a more complex task than trading merchandises. Regarding access to trade finance, lack of collateral to secure financing operations usually excludes enterprises exporting services from those benefits, evidencing a market failure. As shown from the results of the survey and interviews with key stakeholders, limited participation of Chilean service companies in international markets can be partly explained by the lack of available financial instruments for their internationalization process.

Although the results of the survey in this study indicate that access to financing is not the main barrier to exporting services; the traditional banking system, in fact, often has a bias against the service sector. However, when reviewing the current situation of Chilean services exporters, we can find great ignorance about the instruments available to finance international commercial transactions. Most companies exporting services do so with their own funds, as they are unaware of the possibilities in both traditional financial markets and public programs. This limits their capabilities to access third markets, reason why only those companies with high assets or with secure businesses (usually with contracting parties with previous relations within the Chilean market) can export.

It is important to note that the asymmetry of information in the services sector is a growing problem. Although is not the main barrier for services exports, this limits the capabilities of the Chilean government to implement sound policies towards the support of these industries. Therefore, the State must pay special attention to the strengthening of statistical tools that reflect the growing importance of the services sector in the economy. Based on the statistical evidence, the government may be able to design public policies that allow to boost the service sector. It is known that the public sector should deal with actions related to different aspects and factors that strengthen the service sector, including access to trade finance.

Increase in production and export of services is one of the key factors for the insertion of Chile in the development and diversification of global value chains. If the Chilean government seeks to develop a strong services export sector, adequate financial instruments should be available. Since traditional financial institutions can not provide the required schemes, a possible alternative is to invest in the creation of an Export Credit Agency (ECA). The majority of the developed countries have Export Credit Agencies; these agencies mainly offer insurances to support export contracts and guarantees for the allocation of credits (by another financial institution) to the importer/exporter. However, direct financing through credits from this source for the export of goods and services is limited; agencies only intervene in case the exporter's bank cannot provide the financial assistance required for one or more exports.

Notes

1. It is important to note that our sample might have a bias towards companies that have worked with ProChile, as these ones were clearly identified, and they expressed their willingness to participate in this kind of studies more strongly than non-exporting companies. Nevertheless, there was an attempt to balance the sample by including enterprises not having participate of ProChile´s initiatives.

2. A complete version of the survey may be found in https://www.dropbox.com/s/jyclwhw2ei4zlgi/Encuesta%20Financiamiento%20Exportaciones.doc?dl=0

3. Companies were classified according to the following scale, as defined by the Chilean Internal Revenue Service:

• Micro companies: billing between US$ 0 to US$ 1 600 000

• Small companies: billing between US$ 1 600 00 and US$ 16 675 000

• Medium companies: billing between US$ 16 675 000 and US$ 66 700 000

• Large companies: billing grater than US$ 66 700 000

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

References

References

Ahn, J., Amiti, M., & Weinstein, D. (2011). Trade finance and the great trade collapse. The American Economic Review, 101(3), 298-302.

Antras, P., & Foley, C. F. (2015). Poultry in motion: A study of international trade finance practices. Journal of Political Economy, 123(4), 853-901.

Ariu, A. (2016). Crisis-proof services: Why trade in services did not suffer during the 2008-2009 collapse. Journal of International Economics, 98, 138-149.

Auboin, M. (2007). Boosting trade finance in developing countries: What link with the WTO? Staff Working Paper, ERSD-2007-04.

Auboin, M., & Engemann, M. (2013). Trade finance in periods of crisis: What have we learned in recent years? Staff Working Paper, ERSD-2013-01. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/reser_e/ersd201301_e.pdf

Bianchi, C. (2009). How service companies from emerging markets overcome internationalization barriers: Evidence from Chilean services firms. Strategic Management in Latin America Conference, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Borchert, I., Gootiiz, B., & Mattoo, A. (2013). Policy barriers to international trade in services: Evidence from a new database. The World Bank Economic Review, lht017.

Borchert, I., & Mattoo, A. (2010). The crisis-resilience of services trade. The Service Industries Journal, 30(13), 2115-2136.

Brush, C., Edelman, L., & Manolova, T. (2015). The impact of resources on small firm internationalization. Journal of Small Business Strategy, 13(1), 1-17.

Cicic, M., Patterson, P., & Shoham, A. (1999). A conceptual model of the internationalization of services firms. Journal of Global Marketing, 12(3), 81-106.

Chaney, T. (2016). Liquidity constrained exporters. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 72, 141-154.

Gaur, A., Kumar, V., & Singh, D. (2014). Institutions, resources, and internationalization of emerging economy firms. Journal of World Business, 49(1), 12-20.

Greenaway, D., Guariglia, A., & Kneller, R. (2007). Financial factors and exporting decisions. Journal of International Economics, 73(2), 377- 395. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2007.04.002

Grönroos, C. (1999). Internationalization strategies for services. Journal of Services Marketing, 13(4/5), 290-297.

Grönroos, C. (2016). Internationalization strategies for services: A retrospective. Journal of Services Marketing, 30(2).

Hughes, A. (1997). Finance for SMEs: A UK perspective. Small Business Economics, 9(2), 151-168.

Humphrey, J. (2009). Are exporters in Africa facing reduced availability of trade finance? IDS Bulletin, 40(5), 28-37.

InterTradeIreland. (2014). Access to finance for growth, for SMEs on the island of Ireland (I. Ireland, Ed.) http://www.intertradeireland.com/media/AccesstoFinancereportFINAL10.01.14.pdf

Javalgi, R., & Grossman, D. (2014). Firm resources and host-country factors impacting internationalization of knowledge-intensive service firms. Thunderbird International Business Review, 56(3), 285-300.

Javalgi, R., & Martin, C. (2007). Internationalization of services: Identifying the building-blocks for future research. Journal of Services Marketing, 21(6), 391- 397.

Malouche, M. (2009). Trade and trade finance developments in 14 developing countries post September 2008: A World Bank Survey (Policy Research Working Paper, Issue WP 55138).

Manova, K. (2013). Credit constraints, heterogeneous firms, and international trade. Review of Economic Studies, 80(2), 711-744.

McQuillan, D., & Scott, P. (2015). Models of internationalization: A business Model approach to professional service firm internationalization. In Business models and modelling (pp. 309-345). Emerald Group Publishing, Ltd.

Miozzo, M., & Soete, L. (2001). Internationalization of services: A technological perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 67(2), 159-185.

Muûls, M. (2015, 2015/03/01/). Exporters, importers, and credit constraints. Journal of International Economics, 95(2), 333-343. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2014.12.003

O'Farrell, P., Zheng, J., & Wood, P. (1996). Internationalization of business services: An interregional analysis. Regional Studies, 30(2), 101- 118.

OECD (2009). Top barriers and drivers to SME internationalisation (Report by the OECD Working Party on SMEs and Entrepreneurship).

Paravisini, D., Rappoport, V., Schnabl, P., & Wolfenzon, D. (2014). Dissecting the effect of credit supply on trade: Evidence from matched credit-export data. The Review of Economic Studies, 82(1), 333- 359.

Samiee, S. (1999). The internationalization of services: Trends, obstacles and issues. Journal of Services Marketing, 13(4/5), 319-336.

Schmidt-Eisenlohr, T. (2013). Towards a theory of trade finance. Journal of International Economics, 91(1), 96-112.

Shaw, V., & Darroch, J. (2004). Barriers to internationalisation: A study of entrepreneurial new ventures in New Zealand. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 2(4), 327-343

Wagner, J. (2014). Credit constraints and exports: A survey of empirical studies using firm-level data. Industrial and Corporate Change, 23(6), 1477- 1492.

WTO (2015). International Trade Statistics 2015 (International Trade Statistics, Issue).